A building meant to serve as a saloon, we learned last time, morphed into Philadelphia’s first official community health center. It opened at 12th and Carpenter Streets in 1914 and survives today, fixing cars, not babies.

The philanthropic Child Federation reconfigured the place into an experimental demonstration site meant to address the city’s high infant mortality rate. “The large room on the first floor has been divided by a partition into two rooms, the front one being utilized as a receiving office, the rear one as a secretary’s office. Two of the rooms on the second floor are used as physicians examining rooms, and the rooms on the third floor as classrooms.”

Classes in maternal and infant health would become the main events in these new health centers, but could only be effective if they grew in number. And grow they did. By 1916, two more centers opened, one at Front and Tasker Streets (it would subsequently be relocated to Eighth and Winton Streets), another at 1136 North 2nd Street and a fourth at 3101 Grays Ferry Road. By the early 1920s, six more would open in other neighborhoods across the city.

According to Wilmer Krusen, the city’s director of public health, “The Philadelphia plan is to establish health centers or sub-health departments in those sections of the city where infant mortality is greatest and the general infectious diseases are most prevalent.”

Here’s a list of Philadelphia’s first eight health centers, all up and running by 1919:

Health District No. 1 — Twelfth and Carpenter Streets.

Health District No. 2 — Eighth and Winton Streets.

Health District No. 3 — 1136 North Second Street.

Health District No. 4 — Twenty-third and Wharton Streets.

Health District No. 5 — 2624 Kensington Avenue.

Health District No. 6 — 3826 Germantown Avenue.

Health District No. 7 — 5238 Lancaster Avenue.

Health District No. 8 — Front and Tasker Streets

Within a few more years, two additional centers would open at 2016 Lombard Street and 6029 Woodland Avenue.

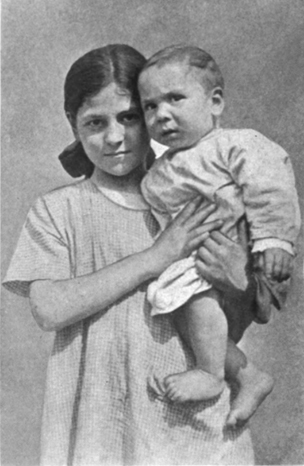

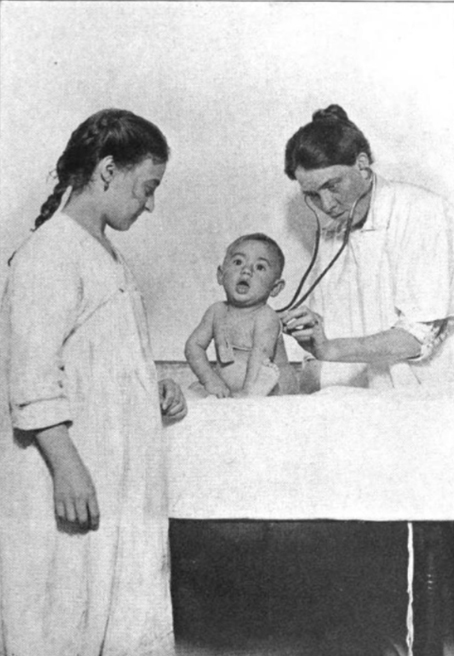

What took place in these facilities? “Mothers are encouraged to bring their babies to the health centers at least once a week where they can be weighed and examined,” wrote Krusen. “Such babies are not treated, but are referred to the family physician, or to a dispensary. Health lectures are frequently planned and exhibits are always open to the public. Health literature, dealing not only with the care of the baby and child but also with the infectious diseases and health matters in general, is freely distributed.”

“The mothers are taught how to nurse their babies and how to detect signs of illness. Where the milk of the baby must be modified, this is explained and performed by the nurse.”

According to Krusen: “The mother, learning that others are interested in her children soon becomes enthusiastic over their progress. They attend the clinic just like children attend school. The centers are thus educational institutions which tend to make better mothers, better babies and better citizens.”

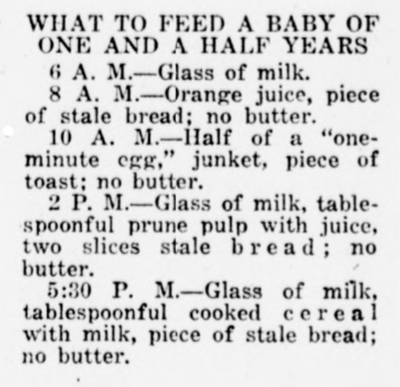

A special pictorial section in The Evening Public Ledger of May 3, 1917 gave a good idea what took place in these health center classes. Municipal nurses Irene Leslie and Betty Chodowski could be found instructing new mothers, grandmothers, and others in attendance at Health Center No. 2 (2128 South Eighth Street) on “how properly to fill the nursing bottle,” the right and wrong way to swaddle babies (enabling circulation and some leg movement) and what to feed an 18-month-old. (The recommended diet and feeding schedule: 6AM: Glass of milk; 8AM: Orange juice, piece of stale bread, no butter; 10AM: half of a ‘one-minute egg,’ junket, piece of toast; no butter; 2PM” Glass of milk, tablespoon prune pulp with juice, two slices stale bread; no butter; and 5:30PM – Glass of milk, tablespoonful cooked cereal with milk, piece of stale bread; no butter.”)

“It is the personal contact between the public and representatives of the health department as accomplished at the health centers which goes a long way toward securing the hearty cooperation of the people in all matters dealing with the protection of the public health,” wrote Krusen. The “health centers in Philadelphia have assumed so many public health functions that they are now considered as local branches of the Health Department.”

By 1917, public health officials counted only about a dozen health centers in the entire country—and the majority were in Philadelphia. Within the next several years, however, nearly 400 American communities would have their own.

And then there was the rest of the world.

“The health center idea has been conceived by public health workers in response to a universal need,” wrote Walter H. Brown, M.D., Associate Director of the American Red Cross. “It is more than a mere coincidence that we find some form of the social device developing almost simultaneously in England, France, Belgium, Wales, Australia, Canada, Cuba—as well as in our own country. This can only mean that we are dealing with an idea of unusual value.”

[Sources: “Illustrating Philadelphia’s Vigorous Campaign to Reduce Summer Baby Mortality,” Evening Ledger – Philadelphia, May 3, 1917 – Accessed via the Library of Congress; Walter H. Brown, M.D. Associate Director, Department of Health Service, American Red Cross, “Symposium on the Health Center III. Present Status of the Health Center,” American Journal of Public Health: JPH, Volume 11, Issue 1, January 1921; 218-220; Wilmer Krusen, M D, LL.D. Director, Department of Public Health and Charities of Philadelphia, “The Health Center Plan in Philadelphia,” Health News, Monthly Bulletin NY State Dept of Health – February 1919; Wilmer Krusen, M D, LL.D. Director, Department of Public Health and Charities of Philadelphia, Progress / Dept of Public Health and Charities Monthly Bulletin – Special Issue – September October November, [1919]; J. A. T. “Symposium on the Health Center. I. The Historical Development.” American Journal of Public Health, Vol 11, No. 3, March 1921, pp. 212-213.]