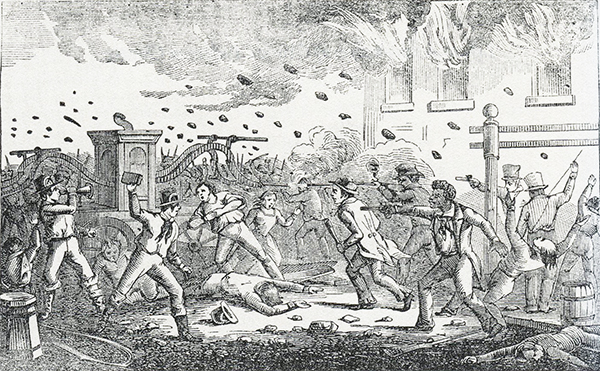

“One of the most dreadful and sanguinary riots” Philadelphia had ever seen—and by 1849, Philadelphia had seen more than a few—took place on an election night. The events were so dreadful and so sanguinary, gothic novelist George Lippard adopted them, without embellishment, as fiction.

Newspapers had the story first: “The California house, at the corner of St. Mary [now Rodman] and Sixth streets, had long been an object of hostility to the whites.” The riot, or ”outbreak,” as some called it, “was one of those sudden explosions of brutal passions, which could not have been foreseen.” But those who the residents of St. Mary’s Street knew better. With gangs like the Killers and the Stingers dominating the streets, they saw it coming.

“It was the whites against the blacks,” another news account tells us. “The keeper of a black tavern, the California house, was charged with having a white woman for a wife, or with living with her as though she was his wife; and to put an end to or to punish this indecency, or this profligacy, or whatever it was, the mob took the matter in hand, and proceeded, as usual, a la Lynch.”

Rear of 714-716 South 7th Street, November 8, 1918. (PhillyHistory.org).

We switch to Lippard’s “fictional” account of the context, and the tumultuous situation:

“On that night the city and districts of Philadelphia were alive with excitement. Every street had its bonfire; crowds of voters were collected around every poll; bar-room and groggery overflowed with drunken men. The city and the districts were astir. And through the darkness of night, a murmur rose at intervals like the tramp of an immense army.

“It was election night. The good citizens were engaged in making a Sheriff who might prove an honest man and a faithful officer or who might heap up wealth, by stolen fees, and leave the county to riot and murder, while he grew rich upon the misery of the people. The good citizens were also engaged in electing Members of Assembly who might go to Harrisburg and do their duty like men, or who might go there as the especial hirelings of Bank speculators, paid to enact laws that give wealth to one class, and poverty and drunkenness to another. There was a stirring time around the State house: the entire vicinity ran over with patriotism and brandy. Vote for Moggs the People’s friend! Vote for Hoggs the sterling patriot! Don’t forget Boggs the hero of Squamdog! Appeals like these glared from the placards on the walls, and flashed from the election lanterns, carried in the hands of sturdy politicians. In fine, all over the county, the boys had their bonfires, the men their brandy and politics, the Candidates their agonies of suspense.”

Lippard continues: “There was one district, however, which added a new feature to the excitement of election night. It was that district, which partly comprised in the City Proper, and partly in Moyamensing, swarms with hovels, courts, groggeries—with dens of every grade of misery and of drunkenness—festering there, thick and rank, as insects in a tainted cheese. It cannot be denied that hard-working and honest people, reside in the Barbarian District. Nor can it be denied that it is the miserable refuge of the largest portion of the Outcast population of Philadelphia county.”

Thanks to the Killers and the Stingers, two of the city’s growing number of gangs, that “district [had] for two years been the scene of perpetual outrage. Here, huddled in rooms thick with foul air, and drunk on poison that can be purchased for a penny a glass, you may see white and black, young and old, man and woman, cramped together in crowds that fester with wretchedness, disease and crime.”

One crime that election day was a bold and brutal attack on the California House.

“Through this district, at an early hour on the night of election, a furniture car, filled with blazing tar barrels, was dragged by a number of men and boys, who yelled like demons, as they whirled their locomotive bonfire through the streets. It was first taken through a narrow street, known as St. Mary street” and rammed into the California House, which was soon aflame.

Again, from Lippard: “Many were wounded, and many killed. It was an infernal scene. The faces of the mob reddened by the glare, the houses whirling in flames, the streets slippery with blood, and a roar like the yells of a thousand tigers let loose upon their prey, all combined, gave the appearance of a sacked and ravaged town, to the District which spreads around Sixth and St. Mary street. The rioters and spectators in the streets were not the only sufferers. Men and women sheltered within their homes, were shot by the stray missiles of the cowardly combatants.”

Where were the police? Occupied elsewhere, throughout the city. It was election night.

“Shortly before midnight,” we learn from the Inquirer, “a body of Police forced their way to the scene of action, fire, and bloodshed,” but the entire area was out of control. Chaos continued into the next morning when “six or eight military companies headed by the Sheriff and Mayor marched to the scene of action, took possession of the disturbed district, and planted cannon in the streets to prevent the encroachment of the crowd.”

Cannon in the streets of the Quaker city? Lippard knew he couldn’t improve on this reality for his fiction.

“There is not a city in the Union more shamefully mob-ridden than Philadelphia,” reported The National Era. This most “mobocratic” city cannot be redeemed from the curse of the mob, wrote Frederick Douglass, who called out the “bitterness and baseness of the hatred with which colored people are regarded in Philadelphia. “

This city is home to the “most foul and cruel mobs” waging war “against the people of color” Douglass continued. Philadelphia “is now justly regarded as one of the most disorderly and insecure cities in the Union. No man is safe—his life—his property—and all that he holds dear, are in the hands of a mob, which may come upon him at any moment—at midnight or mid-day, and deprive him of his all.

“Shame upon the guilty city! Shame upon its law-makers, and law administrators!”

But there was little shame in the city that would, over time, earn notoriety in a book by Lincoln Stephens titled The Shame of the Cities. Philadelphia’s chapter? “Corrupt and Contented.”

[Sources: “Postscript. Dreadful Riot. Houses Burned, and Several Persons Killed and Wounded.” The Philadelphia Inquirer, October 10, 1849; “Mob at Philadelphia,” The Columbia Democrat, October 20, 1849; “A Terrible Riot Took Place in Philadelphia,” Jeffersonian Republican, October 18, 1849; George Lippard, Matt Cohen, and Edlie L. Wong. The Killers: a Narrative of Real Life in Philadelphia. (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2014).]