Shawn Evans, Atkin Olshin Schade Architects

Few recent historic preservation struggles have captured the public’s attention in Philadelphia as dramatically as the Boyd Theatre. Since 1928, this art-deco movie palace has graced the 1900 block of Chestnut Street and entertained millions of Philadelphians in its nearly 2,500 seats.

The theater closed in 2002 and remains vacant. The Friends of the Boyd successfully fought off a demolition permit and continue to advocate for an authentic restoration and viable business approach that will return the theater as a vibrant entertainment venue.[i] The Boyd stands as the last movie palace (a grand theater with more than 1,000 seats) and serves as a stunning reminder of a time when it became common to erect extraordinary architecture for the entertainment of the masses.[ii] A stroll through the history of Philadelphia’s movie theaters demonstrates the importance of saving the Boyd.

B.F. Keith’s Bijou Theatre, seen here as the renamed New Garden

Theatre in 1938.

The first public showing of a motion picture (perhaps the first in the world) occurred in Philadelphia at B.F. Keith’s Bijou Theatre at 209 North 8th Street in 1895.[iii] These films were brief silent experiments of the moving image. Within a year, this new form of entertainment was regularly shown at the Bijou. The 1,200 seat theater was built as a variety theatre in 1889 to the designs of New York theater architect John Baily McElfatrick.[iv] The Bijou was at the heart of a long-vanished theater district along 8th Street, now home to the Gallery Mall, Police Headquarters, and the former Metropolitan Hospital.

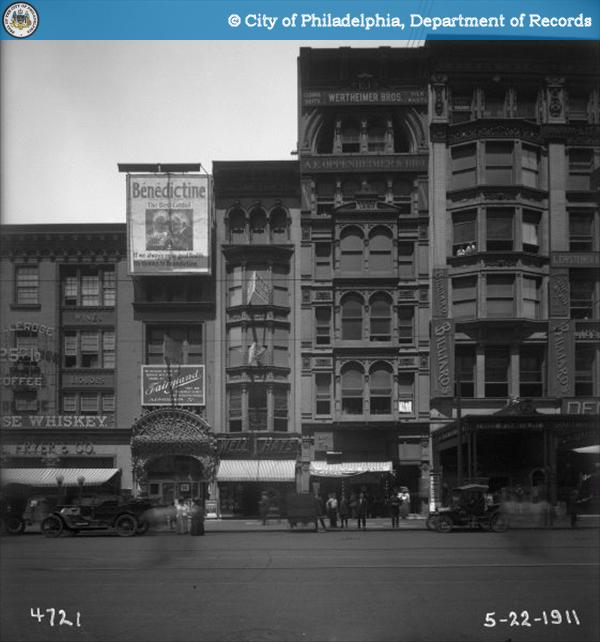

Fairyland Theatre, 1319 Market, seen here in 1911.

Public demand for motion pictures increased quickly and Center City’s commercial streets were soon home to hundreds of store-front nickelodeons. 136 of these small theaters opened in Philadelphia between 1905 and 1917, most of which were only open a few years. Seen here in a 1911 photo is the Fairyland, a nickelodeon that operated at 1319 Market Street from 1909 to 1913. The sign above the elaborate entrance reads, “No pictures in the city compare with films shown at Fairyland – They are the newest, cleanest, and most interesting produced. Admission 5¢.”[v]

The Stanton, 1620 Market Street, seen here in 1935.

The advent of full-length feature films in the 1910s brought the downfall of nickelodeons, as bigger theaters were now needed that were capable of comfortably seating larger audiences for longer periods of time. 275 movie theaters were opened in Philadelphia through 1932. The finest of the movie palaces were located in Center City, although many were built in the outlying neighborhoods.[vi] One of the first palaces was The Stanton, erected in 1914 at 1620 Market Street to the designs of W.H. Hoffman. Hoffman later partnered with Paul J. Henon Jr. in the Hoffman-Henon Co., one of America’s most prodigious theater designers. They designed over 100 theaters, including the Boyd Theatre and 46 others in Philadelphia. The 1,457 seat Stanton was originally named The Stanley, for Stanley Mastbaum of the Stanley Corporation, who by 1920 was the largest theater operator in the country. During the era of silent pictures, the Stanton featured a full orchestra. The theater was renamed The Milgram in 1968 and was demolished in 1980.[vii]

The Stanley, 19th and Market, seen here in 1935.

The second theater named the Stanley opened at the southwest corner of 19th and Market in 1921. The 2,916 seat movie palace was designed by the Hoffman-Henon Co. The new Stanley was also host to musical offerings and had its own renowned orchestra. While the building’s exterior and interior were designed in pure classical traditions, a tremendously exuberant illuminated sign covered much of the Market Street façade.[viii] The most famous event at the Stanley had nothing to do with film –Al Capone was arrested here in 1929. The Stanley was demolished in 1973 and the Philadelphia Stock Exchange opened on this site in 1982.

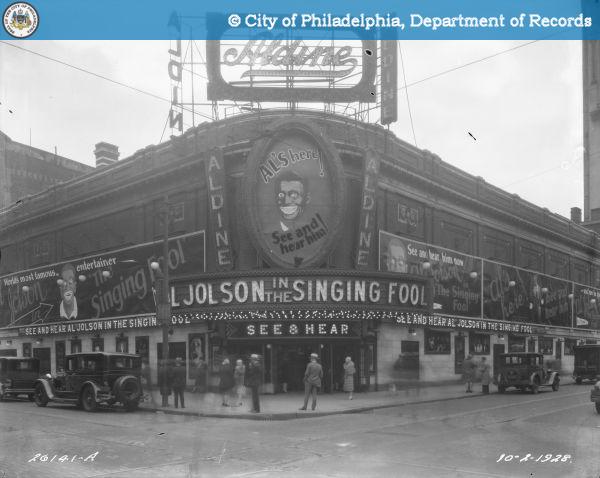

The Aldine Theatre, seen here in 1928.

One of the few movie palaces that still embellishes Center City sidewalks is the Aldine Theatre, at the southeast corner of 19th and Chestnut, although it stopped operating in 1994 and is now a CVS. Designed by William Steele & Sons, Architects, this 1,341 theatre later cycled through a series of names such as the Viking, Cinema 19, and finally Sam’s Place in 1980 when its ornate interior was divided into two separate theatres.[ix] This theater is the subject of another PhillyHistory Blog entry, “See and Hear the World’s Greatest Entertainer,” which focuses on the nature of blackface seen so prominently on the theater’s exterior.[x]

The Karlton Theatre, 1412 Chestnut Street, seen here in 1935.

The Karlton Theatre, 1412 Chestnut Street, was another Hoffman-Henon Co. theater that opened in 1921. Constructed behind a c.1880 second-empire style façade, the elaborate interiors were decorated in the classical style and featured extensive use of marble, murals, tapestries, and gilding. Renamed the Midtown Theatre in 1950, the historic façade was concealed behind plastic siding and its interiors stripped. The 1,066 seat theater was eventually twinned and in 1999 was renovated as the Prince Music Theatre.[xi]

The Fox Theatre, 16th and Market, seen here in 1959.

Several of Philadelphia’s finest movie theaters were built within larger commercial structures. The Fox Theatre opened in 1923 next door to the Stanton at the southwest corner of 16th and Market. Designed by the noted New York theater architect, Thomas W. Lamb, the 2,423 seat Fox was home to both film and elaborate stage shows, featuring an in-house orchestra.[xii] Demolished in 1980, the Fox inspired an ultimately unsuccessful preservation fight as it was recognized that the Fox was the last of the grand neoclassical movie palaces.

The Erlanger Theatre, 21st and Market, seen here in 1938.

The Erlanger Theatre occupied the northwest corner of 21st and Market Streets from 1927 to 1978. Built primarily for legitimate theatre, it also showed film. The 1,890 seat Erlanger was another Hoffman-Henon theater, and featured eclectic interiors in Spanish, French, and English styles.[xiii] The photograph below documents illegal signage. During the 1930s, the Philadelphia Art Jury, the predecessor to the Art Commission, enforced strict standards on commercial signage which resulted in the loss of many extraordinary marquees and signs, including the 30’ tall vertical blade sign on the Boyd Theatre, which was removed around 1935.

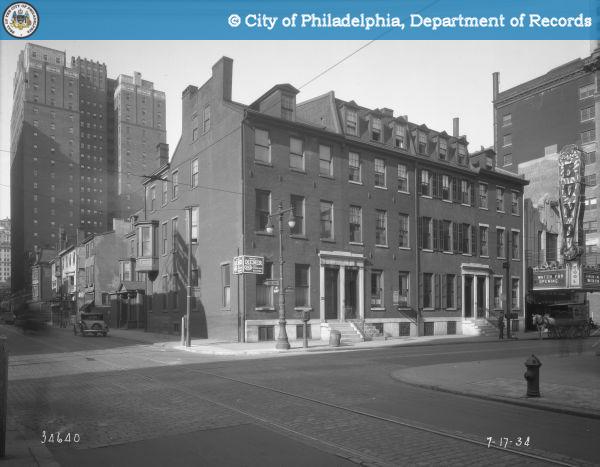

The Boyd Theatre, 1908 Chestnut, seen here in 1934.

The Boyd Theatre was the next major movie palace to open in Center City in 1928 and the only downtown movie palace designed in the Art-Deco style. While eclectic styles such as Spanish and North African had been used for theaters in outer neighborhoods, the previous downtown theatres had all been built in more rigid classical styles. The Boyd represents the acceptance of more “modern” styles. This 1934 image captures a happenstance that reinforces the modernity of the Boyd – a horse-drawn wagon selling milk and ice cream passes by the marquee advertising that the theatre is closed for the summer for the introduction of air-conditioning. The letters B-O-Y-D have been replaced with C-O-O-L on the corners of the marquee. While the Boyd was designed to accommodate “talkies,” it was still equipped with a small stage and orchestra pit, needed for the presentation of silent films.

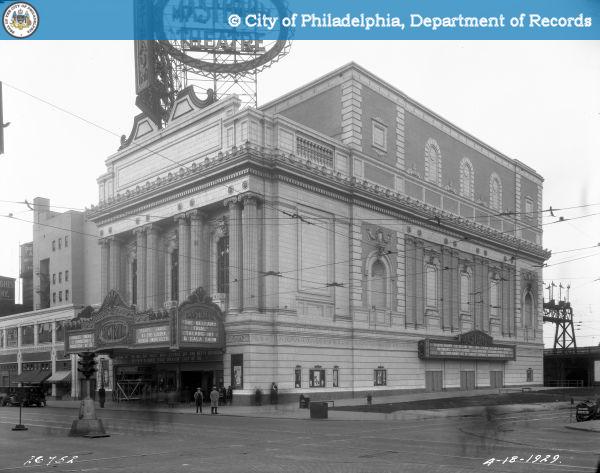

The Mastbaum Memorial Theatre, 20th and Market, seen here

in 1929.

The last and largest of Philadelphia’s downtown movie palaces was the Mastbaum Memorial Theatre, built at 20th and Market in 1929. This 4,700+ seat (!) theater was another Hoffman-Henon design.[xiv] It was an outrageously expensive anachronism from the moment it opened. The end of silent films made presenting films much simpler and the audience could more easily be transported to another place or time without need for such elaborate architecture. After only 29 years of entertainment, this palace met the wrecking ball – one of the first of these grand theaters to go.

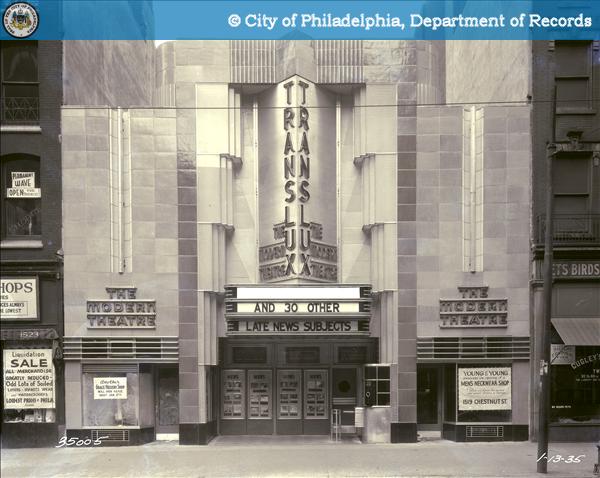

The Trans-Lux Theatre, 1519 Chestnut Street, seen here in 1935.

For the most part, the era of these elaborate buildings was over even before the Great Depression began. The economy would dry up both financing for construction and the growth of expensive forms of popular entertainment like legitimate theater, but film remained a good business as ticket prices were so low. Smaller theaters continued to be built. Perhaps the last dramatic theater building in Center City was the Trans-Lux Theatre, erected in 1935 at 1519 Chestnut Street. [xv] Designed by Thomas Lamb (architect of the Fox as well), this 493 seat theater was a vibrant expression of the new through its Art-Moderne style. The Trans-Lux survived as a theatre until 1993, then operating as Eric’s Place. Perhaps this remarkable façade lies underneath the 1970 white and black siding of the building, now occupied by the Finish Line sporting goods store.

The economics of the motion-picture business today make it unlikely that the few surviving structures will be restored solely for film, yet these buildings retain a powerful hold on the collective imagination. We are unwilling to let them go. Like the damsels in distress tied to the railroad tracks in so many of the movies that played inside, their future is momentarily uncertain. We await creative rescue plans that can return these buildings to the public.

Thanks to Howard B. Haas for reviewing this and making helpful comments.

References

[i] BOYD: See the Friends of the Boyd website for more information, history, and photos: http://www.friendsoftheboyd.org/index.html Additional information on the building can be found here: http://www.philadelphiabuildings.org/pab/app/pj_display.cfm/12550 and http://cinematreasures.org/theater/1209/

[ii] Irvin Glazer (1922-1996) documented the history of Philadelphia theaters in two books: Philadelphia Theaters: A Pictorial History (Dover Publications, 1994) and Philadelphia Theatres, A-Z: A Comprehensive, Descriptive, Record of 813 Theatres Constructed Since 1724 (Greenwood Press, 1986). His collection of photographs, clippings, and research files is housed at The Athenaeum of Philadelphia. Most of the photographs have been scanned and are available online in a format that permits zooming. http://www.philadelphiabuildings.org/pab/app/co_display.cfm/483480?CFID=60415619&CFTOKEN=31750787

[iii] Glazer, Philadelphia Theaters: A Pictorial History, p.xxii.

[iv] BIJOU: http://www.philadelphiabuildings.org/pab/app/pj_display.cfm/8126

[v] FANTASYLAND: A similar zoom-able image can also be found at http://www.philadelphiabuildings.org/pab/app/pj_display.cfm?RecordId=AFA0B8B0-5A85-4AE6-8880AC8D08FDE994

[vi] The neighborhood theatres are different in character and just as interesting, but this blog entry focuses on the theaters in Center City.

[vii] STANTON: Glazer, p.17. See also: http://www.philadelphiabuildings.org/pab/app/pj_display.cfm/5907 and http://cinematreasures.org/theater/3393/

[viii] STANLEY: Glazer, pp.26-27. See also: http://www.philadelphiabuildings.org/pab/app/pj_display.cfm/19220 and http://cinematreasures.org/theater/4526/

[ix] ALDINE: Glazer, p.27. See also: http://www.philadelphiabuildings.org/pab/app/pj_display.cfm/8622 and http://cinematreasures.org/theater/3358/

[x] https://phillyhistory.wpengine.com/index.php/2006/06/see-and-hear-the-worlds-greatest-entertainer/

[xi] KARLTON: Glazer, pp.28-29. See also: http://www.philadelphiabuildings.org/pab/app/pj_display.cfm/6878 and http://cinematreasures.org/theater/1803/

[xii] FOX: Glazer, pp.31-33. See also: http://www.philadelphiabuildings.org/pab/app/pj_display.cfm/5520 and http://cinematreasures.org/theater/1177

[xiii] ERLANGER: Glazer, pp.42-45. See also: http://www.philadelphiabuildings.org/pab/app/pj_display.cfm/12547 and http://cinematreasures.org/theater/22732/

[xiv] MASTBAUM: Glazer, pp.70-78. See also: http://www.philadelphiabuildings.org/pab/app/pj_display.cfm/6244 and http://cinematreasures.org/theater/1207/

[xv] TRANS-LUX: This photo shows the site just three months earlier: http://www.phillyhistory.org/PhotoArchive/Detail.aspx?assetId=14907. See also: http://www.philadelphiabuildings.org/pab/app/pj_display.cfm/7212