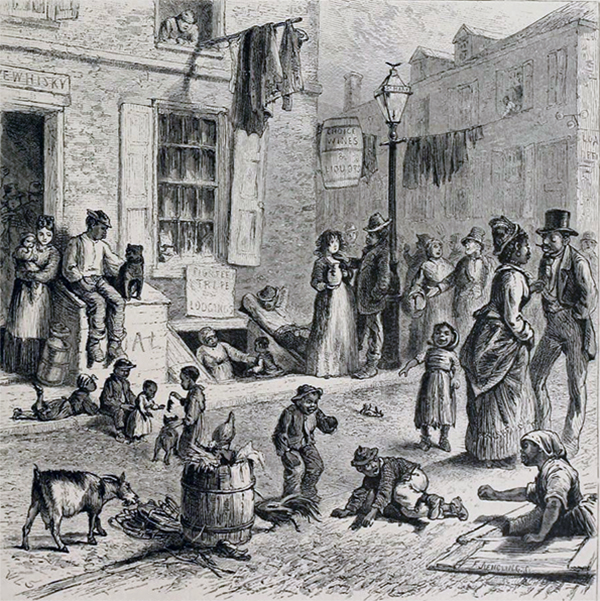

In the 1890s, sociologist W.E.B. DuBois and his wife moved to the 600 block of Rodman Street, known then as Carver Street, and previous to that, St. Mary Street. Here, in what DuBois called “the worst Negro slums of the city” he went door-to-door documenting the city’s so-called “Negro problem” or, as he preferred to call it, “the submerged tenth.” Philadelphia’s notorious 7th ward had long been known as the city’s most impoverished, crime-infested, disease-ridden. And in his landmark study, The Philadelphia Negro, published in 1899, DuBois reported on the full spectrum of residents, including the “the working class,” “the poor” and the “vicious and criminal class.”

The latter made a most lasting impression. “Murder sat at our doorsteps,” DuBois later recalled. Everyone remembered (or had heard tell of) the violent demise of the California House the tavern attacked and burned by a mob in 1849. That raw incident served as inspiration for George Lippard’s novel, The Killers. A quarter century later, St. Mary Street served as a gritty counterpoint to the Centennial celebration, an urban scene ridden with “squalor, filth, misery, and degradation.”

In the first years of the 20th century, this would become the place Henry Phipps, steel magnate turned philanthropist, imagined as ground zero for making positive change with the construction of a new hospital dedicated to the study and treatment of tuberculosis. Phipps and his medical experts knew that the rate of fatalities from tuberculosis, the leading cause of death in the city’s Black neighborhoods was as much as quadruple its rate in white communities.

With a commitment of $1.5 million (equivalent to nearly $50 million today) Phipps and his team had every reason to believe they could significantly reduce the impact of tuberculosis in Philadelphia’s poorest, most afflicted neighborhood. All it would take, Phipps believed, was education, training and therapies administered by a fully staffed and properly equipped brick-and-mortar hospital.

In 1903, the Henry Phipps Institute opened its temporarily quarters at 238 Pine Street. A decade later, the Institute moved to a new, larger fully staffed facility at the northeast corner of 7th and Lombard Streets – just around the corner from old St. Mary Street – in the belly of the urban beast.

This was a new strategy for Phipps, who in previous years, attacked the scourge of tuberculosis by creating a tuberculosis sanatorium in White Haven, Pennsylvania, a rural borough about 100 miles to the north. But in time, Phipps came to realize that transporting sick and dying patients away from the city’s most diseased neighborhood to a far-flung pastoral setting wouldn’t result in permanent change in the slums of Philadelphia.

Lasting change, the Phipps team believed, would be more likely with cutting edge treatments administered at home in a large, purpose-built multi-storied hospital that looked like it belonged. Phipps hired New York architect Grosvenor Atterbury to design for 7th and Lombard Streets, a red brick building with “marble finishings along old Philadelphia colonial lines.” One wing was devoted to research; other housed resident physicians, dispensaries, waiting rooms, and classrooms. Four wards and adjacent porches facilitated all-important access to sunlight and fresh air. With these neighborhood-based interventions, the Phipps team believed it would be only a matter time before tuberculosis in Philadelphia was under control, if not eradicated.

But neighbors and even some medical professionals objected to this strategy. At a protest meeting one physician from Jefferson Medical College suggested, in a “vigorous speech” that such a facility in the heart of the city would dangerously increase the presence of the fatal pathogen. A petition opposing the Phipps Institute at 7th and Lombard garnered 800 signatures.

The Institute, insisted Lawrence Flick, Phipps’ medical director, would have to be built in Philadelphia. And “if this city does not appreciate the good that would accrue from such an institution,” the donor would take his funding to New York.

“One of the chief purposes” of a Philadelphia-based institution, Flick affirmed, is that medical professionals would “keep in close touch with the poorer classes, and this [could] only be accomplished by having it located in the midst of their homes.” Not only should the Institute built in the city, it should be sited “in a crowded section.” That was Phipps’ “unqualified wish.” Groundbreaking remained on schedule in July 1911. The new structure opened with fanfare in the Spring of 1913.

But before the new Institute could succeed there would be one more barrier to address.

Many suffering with tuberculosis, including and especially Black folks, chose to shun professional medical help and remain at home. Without patients, no amount of philanthropic generosity, cutting-edge hospital design and medical professionalism would be able to overcome longstanding mistrust of medicine. The Institute’s Dr. Landis later recalled this dilemma: “A few Negro patients came to the Institute… [but] in a dying state. Fewer still visited the dispensary, paid one or two visits, and then passed out of sight.” During the decade before the new building opened, the average annual number of Black patients served by the Institute was only 51.

What could be done to achieve a change in public perception and participation? What would it take to finally achieve change in the belly of the urban beast?

The solution, it turns out, was hiding in plain sight.

In early 1914, shortly after the new hospital opened, its managers hired a Black nurse for the first time. Her name was Elizabeth Tyler.

(Sources: “Henry Phipps Institute,” January 10, 1903, The New York Times; From The Philadelphia Inquirer: “Mr. Phipps Gives Over a Million for a Hospital,” January 10, 1903: “No compromise on hospital site,” January 13, 1903; “Oppose Hospital,” January 30 1903; “Against Phipps’ Institute,” February 6, 1903; “Phipps Institute Will Open To-Day, ”February 9, 1903; “Opposition is Dead,” February 13, 1903; “Clear Site for Institute,” October 5, 1909; “To Build Hospital for Consumptives,” July 9, 1911; “Phipps Institute, Enemy of White Plague, to Open,” May 4, 1913; “50 Years at Phipps,” February 1, 1953. Philadelphia Builder’s Guide, v. 26, No. 16, p. 247, April 19. 1911. H.M.R. Landis, “Tuberculosis and the Negro,” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, November 1928; J. Margo Brooks Carthon, “Life and Death in Philadelphia’s Black Belt: A Tale of an Urban Tuberculosis Campaign, 1900–1930,” Nursing History Review. Vol. 2011; 19: pp 29–52.)

For more about tuberculosis in Philadelphia: here and here.

2 replies on “Making Change in the Belly of the Beast ”

Will we learn Ms Tyler’s story?

Absolutely. Stay tuned.