Alba Johnson, president of the Baldwin Locomotive Works, believed Philadelphia was due for “a moral awakening.” Citizens had drifted away from “the virtues which made the American people what they are: purity, modesty, contentment and thrift.” An obsession with material things, which Johnson characterized as “the universal craze for riches,” sapped the city’s “moral strength.” Philadelphia needed “civic reform.” But first, there would have to be a concerted effort to “reform men’s souls.”

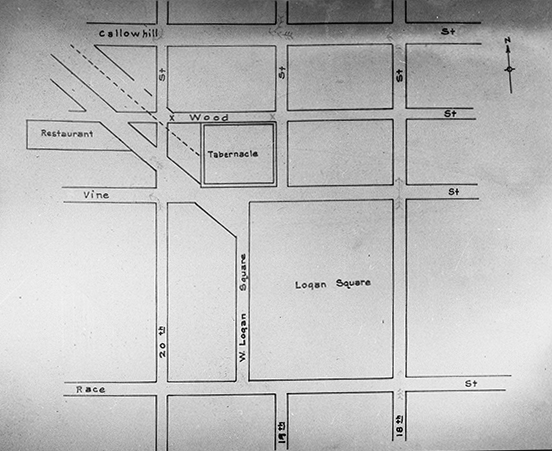

In 1915, Johnson joined other makers and shakers to fund the construction of a giant tabernacle on the north side of Logan Square, where the Free Library now stands. From the inside, this temporary wood and tar paper structure looked like “a miniature forest of timbers.” It seated 20,000 and thousands more would stand in eight spacious aisles that converged at a large open space in front of the podium. The aisles were covered daily with fresh sawdust.

Billy Sunday, America’s “greatest high-pressure and mass-conversion” evangelical preacher, operated twice daily in this tabernacle, January into March. In all, more than 1.8 million turned out for Sunday’s 147 sermons. And more than 44,000 found themselves inspired to walk the “Sawdust Trails,” confirming their faith in a handshake with Sunday.

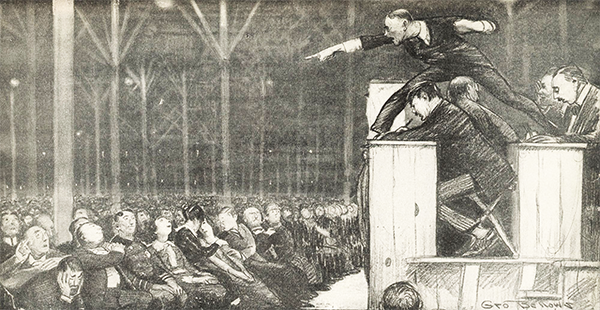

At the front was a 10-foot wooden platform with a small, steel-reinforced pulpit that Sunday would regularly climb to emphasize a point in his sermon. Sunday had played professional baseball before ending his athletic career in Philadelphia in the early 1890s and his continued athleticism marked him as “the acrobatic dervish of evangelism.” His traveling entourage always included a trainer.

Hours before the start of each service, hawkers fanned out for blocks, barking “Git yer hymn-book here! Git yer only authorized life of Billy Sunday!” As packed trolley cars approached 19th and Vine, conductors announced: “Backsliders get out here.” One visitor compared the atmosphere to that of a circus.

Inside, a choir of 1,800 voices started with “Stand Up For Jesus” followed by “Brighten the Corner Where You Are.” Then Sunday walked on stage, charmed the audience, and launched into an animated sermon against the evils of a modern, open society, the “whiskey kings, the German warlords, slackers, suffragettes or the local ministry.”

“He begins to dance like a shadow boxer,” observed journalist John Reed. “He slaps his hands together with a report like a broken electric lamp. He poses on one foot like a fastball pitcher winding up. He jumps up on a chair. In the stress of his routine he may stand with one foot in the chair and another on the lectern.”

“Sunday’s whole sermonizing scheme is worked out to science,” reported The Public Ledger. “He half hypnotizes his congregation with his booming demonic roars, which reached the furthest corner of the squat-roofed structure.”

“‘Come on,’ he shouts. ‘Come on, now.'” “Say ‘Yes’ to God. That’s all. He wants you; you want him! You’re going to hell! Come on, come on to him! Don’t sit there like fools. Hurry up! Come!!!”

Then the choirmaster started “an old time hymn, plaintive and soft, and a woman, sobbing, wavers down the aisle.”

“Are you coming?” yells Sunday, looking right at you or seeming to. “Jesus is here.” “And then the rush begins and finishes in a near fight for salvation. It seems so easy to be saved, so absurd to remain wicked. The rough Sunday charm “refers to God, Jesus Christ and the Holy Ghost as if he rooms with them or had just bought them lunch.”

“He was red in the face now,” noted Reed, “and the sweat was pouring from him” as he climbed onto the pulpit, “sliding from one end of the platform to the other, crouching like a runner, leaping, crouching, every movement as graceful as a wolf’s.”

“He shakes his fist … and cries: ‘Christ is in this city! He has seen every stone laid in Philadelphia. He has heard every lie; seen every false vote; known every vicious thought; every sneer at high and holy things; every yielding to low ideals; Every corrupt practice, every oath, every theft.'”

“Sunday suddenly flung himself across the platform like a baseball player sliding for second.” “‘It’s too late, Philadelphia! . . . It’s too late! Come to Jesus!'”

“Do you know anybody you want to be saved? Stand up! Have you a husband, wife, children, that you would like to see converted?” Throughout the tabernacle they rose by hundreds. “Brother!” they shouted. “Sister!” “My babies! “My husband!”

“God will take you all! “cried Sunday. “Who is coming to Jesus Christ!”

“At the climax,” observed Reed, “the willing and the indifferent hit the ‘Sawdust Trail’ together. The willing came with the merest prompting, fluttering in emotional states of tears of joy, to shake the hands of the evangelist and to sign the convert’s card. The indifferent were usually locked in the arms of one or more herders, experts who discharged their duties in the task of swelling the ranks of those who came forward, whether they signed up or not.”

Sunday described those eleven weeks in Philadelphia as the “Jim-Dandiest” campaign of his preaching career.” Souvenir-seeking followers agreed. As the tabernacle emptied out for the last time, “Men and women pulled down signs from the tabernacle posts and carried them away. They scooped up big handfuls of sawdust from the shadow of the pulpit, filled their pockets and their handkerchiefs with it and carried it home. They took the tin pans which have gathered the tabernacle offerings. They tore the bunting and flags from the rostrum, the flowers from the pulpit; they carried away everything loose that could serve as mementos of the campaign.”

In the weeks after Sunday’s departure, thousands of his converts swelled the church pews of Philadelphia. Ministers of all denominations estimated an increase of as many as 80,000 new members. But would they last? And, more to Alba Johnson’s hope, had Billy Sunday reformed even a single soul? And whatever would become of the idea for “civic reform”?

[Sources: “Find inspiration in “Billy” Sunday: Rev. J. H. Jackson tells of visit to Philadelphia tabernacle,” The Hartford Current, February 15, 1915; “Billy Sunday has preached to nearly 2,000,000 persons in Philadelphia,” The Washington Post, March 9, 1915;”Billy Sunday closes record campaign in Philadelphia,” Chicago Daily Tribune, March 21, 1915 (Originally published in The Public Ledger.); “Billy Sunday saves 41,724; get $51,136.” Chicago Daily Tribune, March 22, 1915; “The end of Billie Sunday’s Philadelphia campaign,” The Sun, March 22, 1915; “Statistics of the Rev. Billy Sunday‘s great campaign in Philadelphia,” The Washington Post, March 23, 1915; “Back of Billy Sunday,” by John Reed. Metropolitan, v. 42, May 1915; “Billy Sunday dies; evangelist was 71”, The New York Times, November 7, 1935.]

One reply on “Billy Sunday’s “Jim-Dandiest” Evangelical Campaign”

Nothing has changed since 1915 except that Joel Osteen has replaced Billy Sunday.