Mayor Rudolph Blankenburg made a promise. His administration would be non-partisan. At the inaugural in December 1911, according to historian Lloyd M. Abernethy, Blankenburg proposed to operate “on a sound business basis with experts rather than politicians at the heads of municipal departments.” The mayor “surrounded himself with able and dedicated professionals” and spent four years envisioning, modernizing and improving city services—especially mass transit.

Philadelphia had 600 miles of streetcar lines, but the passenger experience was slow and disconnected. The city’s “meagre 14.7 miles of high-speed trackage compared very unfavorably with other major cities: Boston had twice as much; Chicago, 10 times more; and New York 20 times as much.” Blankenburg recruited an experienced railroad executive, A. Merritt Taylor, to direct his new transit department. And Taylor immediately took a deep dive assessing the situation and developing a comprehensive, city-wide plan that would quadruple the city’s high-speed trackage to nearly 60 miles.

It took two years for Taylor to complete his study and present his vision for a mass transit system. In an essay entitled “Philadelphia’s Transit Problem,” Taylor pointed out that “large cities of the United States are constantly outgrowing the capacity of existing facilities for public service.” These systems “may be likened to the arterial system of the human body.” They can “become inadequate and choke the circulation which they are designed to carry.” They often “fail to expand as the body grows” falling short of meeting the city’s “increasing requirements.” That, Taylor said, would lead neighborhoods to “wither.”

Without a healthy transit system, “the body as a whole must suffer.”

Philadelphia, Taylor pointed out, wasn’t a city of tenements and flats. Rather, it “has always been a city of individual homes spread over a comparatively large area.” Now we are “confronted with the necessity of providing rapid transit facilities to eliminate existing congestion of traffic and the excessive loss of time in traveling the increasingly great distances between available residential areas and places of employment.”

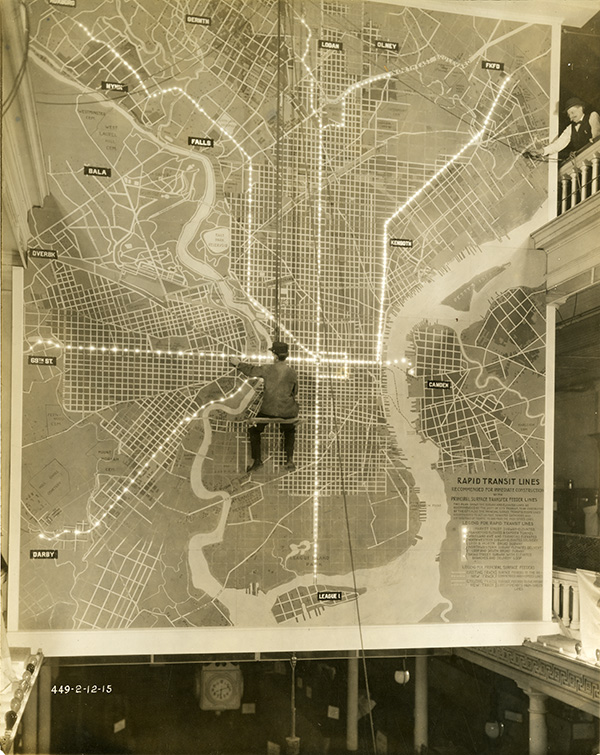

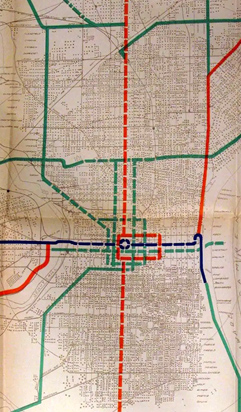

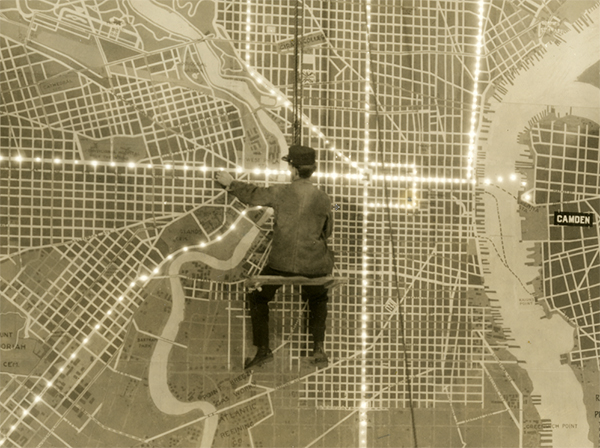

This “practical, scientific and complete study of what is needed” led to a series of “crystallized” recommendations in a report published in 1913. To sell his plan, Taylor and his allies released a battery of illustrated articles, maps and presentations—including a giant, electrified model.

Taylor’s “program,” wholeheartedly endorsed by Mayor Blankenburg, urged the immediate construction of twenty-six miles of high-speed lines, subway and elevated, that would effectively connect with the existing “surface system” extending “the advantages of rapid transit … as equally as practicable to every front door in Philadelphia.”

“Passengers will be enabled to travel in a forward direction … between every important section of the city and every other important section of the city, conveniently, quickly and comfortably by way of the combined surface and high-speed lines, regardless of the number of transfers required in so doing.”

At the groundbreaking for the Broad Street Subway, the first major element in the plan, Taylor asked the public to think of the system as “one great machine [designed to] transport passengers quickly and conveniently between all points on the combined system . . . by the joint use of the surface system and the high-speed system for one five-cent fare.”

“Any citizen could ride from any part of Philadelphia to any other part of the city, for five cents and within thirty minutes time,” echoed the mayor. “When such a condition becomes an accomplished fact, then our great body of skilled labor, 300,000 strong, can choose its residence in any part of the city, irrespective of the location of the factory or office in which they find employment.”

The cost of the system: about $46 million, with another $12 million more for equipment. (In today’s dollars, that would be an investment of $1.5 billion). Without delays, according to the mayor, “these high-speed lines could be in active operation by 1919 or 1920, thereby giving Philadelphia one of the most comprehensive transit systems in the world.”

But as was often the case, politics trumped transformation.

After many delays, the Broad Street Subway opened in 1928. By then, the “Taylor Plan” was largely abandoned. The system’s most visionary element—possibly its proudest single feature—a subway-surface line running from City Hall, under Logan Square, up the Parkway to the Art Museum before travelling north on 29th Street to Henry Avenue and beyond to Roxborough . . . never materialized.

[Sources: A. Merritt Taylor. Report of Transit Commissioner: City of Philadelphia, July, 1912. [Philadelphia, 1913], Vol 1; “Taylor Plans $57,578,000 Transit Development for Philadelphia.” The Philadelphia Inquirer, July 31, 1913; Conference of American Mayors, Philadelphia, and American Academy of Political and Social Science. “Proceedings of the Conference of American Mayors on Public Policies as to Municipal Utilities,” (Philadelphia, American Academy of Political and Social Science, 1915); “Mayor Launches Work on Subway as Crowd Cheers,” The Philadelphia Inquirer, September 12, 1915; A . Merritt Taylor. “Philadelphia’s Transit Problem.” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 57 (1915): 28-32; Donald W. Disbrow. “Reform in Philadelphia Under Mayor Blankenburg, 1912-1916.” Pennsylvania History: A Journal of Mid-Atlantic Studies 27, no. 4 (1960): 379-96; Lloyd M Abernethy, “Progressivism, 1905-1919,” in Russell Weigley, Philadelphia: A 300 Year History (W. W. Norton & Company, 1982).]