Ellen Phillips Samuel had a vision she’d never get to see. After her death and that of her husband, a sizeable chunk of the family fortune would become an endowment to create a sculpture park along Kelly Drive between Boathouse Row and the Girard Avenue bridge.

“On top of this embankment,” wrote Samuel in 1907, “it is my will to have erected at distances of one hundred (100) feet apart, on high granite pedestals of uniform shape and size, statuary emblematic of the history of America, ranging in time from the earliest settlers of America to the present era, arranged in chronological order, the earliest at the south end, and going on to the present time at the north end.”

American art had never encountered such a challenge—or such an opportunity. In Europe, only the Siegesallee in Berlin, completed in 1901, might have provided something of a model. But this massive, white-marble creation was mocked as over-indulgent and vulgar, an “Avenue of the Puppets,” a collection of “shining marble horrors…enough to rob Berlin of sleep.” Not something to emulate in United States—or anywhere else, for that matter.

Samuel did have a handle on the depth and range of American history. Her ancestors aided the cause of the American Revolution and were interred at the Mikveh Israel cemetery near 9th and Spruce Streets where she and her husband were involved as stewards. At family gatherings, the Samuels doubtless debated the who’s who of American history. Her husband’s nephew and namesake, Bunford Samuel, compiled 40,000 portraits of historical figures over a twenty year period. The younger Bunford’s “Index to American Portraits” cataloged no fewer than 58 portraits of Christopher Columbus, 61 of Benjamin Franklin, 16 of Alexander Hamilton and 14 of Benedict Arnold. Would any of them find a home on the proposed pedestals along the Schuylkill? Ellen Samuel was too savvy to dictate that. There would have to be significant discourse before any decisions were made. Along the way, the project might even become controversial, making it even more interesting, and perhaps all the more valuable.

To start the search process, Samuel would solicit proposals in a global crowdsourcing effort. “It is my desire that notices be inserted in the leading newspapers of the world, asking for designs.”

How would American history be represented along this stretch of Schuylkill in America‘s most historic city? After Ellen Samuel’s passing in 1913, J. Bunford couldn’t contain his anticipation, or his mistrust, that others might not stay true to his wife’s wishes. He reminded would-be designers that “Mrs. Samuel never intended that any artificial construction, or that standing trees should be removed to carry out her idea and ruin the sylvan beauty now existing in this locality…” This would not be a project dominated by balustrades or any architectural elements. According to Samuel, only historical figures on pedestals would stand amidst the park’s foliage.

And to make absolutely certain the project would begin as it was supposed to, Samuel got ahead of things and commissioned the first figure. In keeping with the spousal will that the series begin with “the earliest settlers of America,” Samuel selected the 11th-century Icelandic explorer and colonist Thorfinn Karlsefni who, according to his own research, “came nearest to the ideal.” By demonstrating the start of the project, Samuel would be able “to see, whilst I live, how the first statue would look placed in the situation selected by my wife…”.

At the Karlsefni dedication in 1920, the president of the Fairmount Park Art Association, Charles J. Cohen, reassured all in attendance that this first figure in the sculptural timeline would “be followed by… seventeen of similar proportions, all…emblematic of the history of America” standing 100 feet apart, as the will dictated. When complete, added Cohen, this memorial would make “a splendid adornment to our Park.”

Then, as the will directed, the project went into hibernation until after J. Bunford’s passing in 1929. After it restarted, critic Dorothy Grafly noted: “No sculptural project within recent years had posed so many problems and stirred so much discussion.” The Art Association’s Samuel Memorial Committee reviewed all options and would set the direction. One member of the committee, R. Sturgis Ingersoll, later recalled its activities and inclinations and how, ultimately, the project strayed from Samuel’s will.

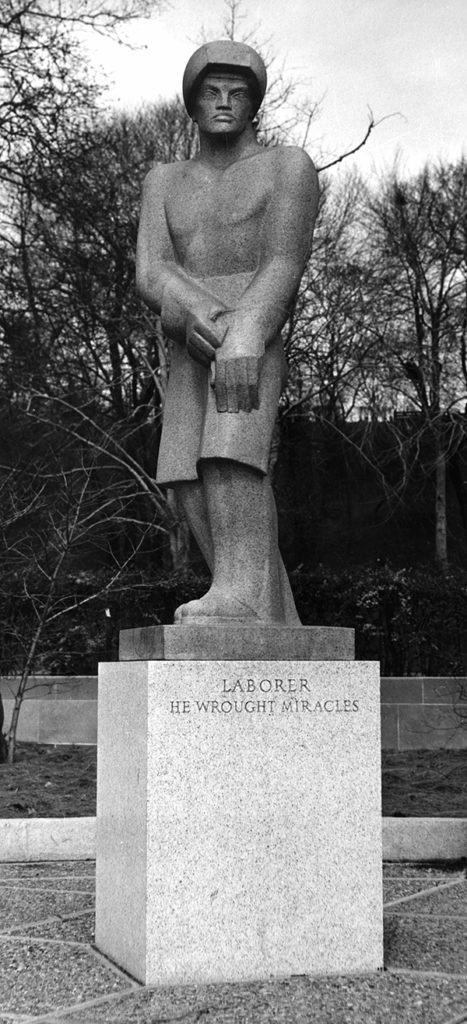

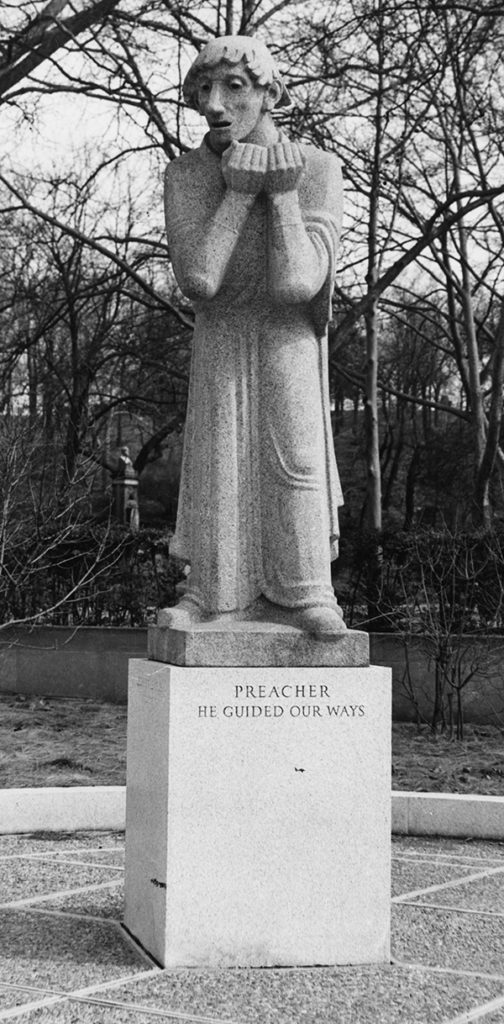

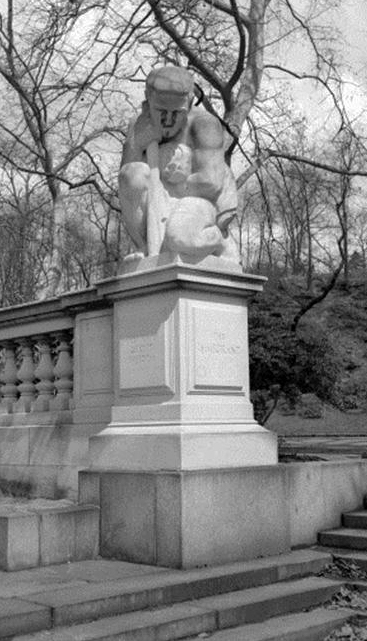

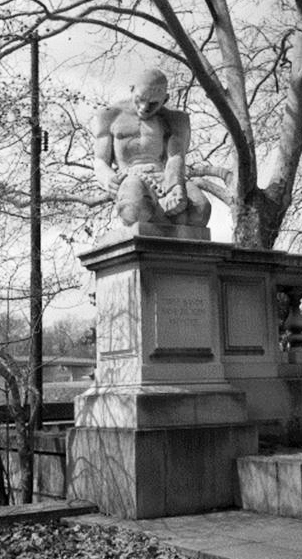

“For several years,” wrote Ingersoll, “the alternatives seemed to be to erect a row of portrait statuary of the important political and spiritual shapers of our destinies, or sculptural symbols of such abstractions as Faith, Democracy, Wisdom, Patriotism and Justice.” But the committee took a broader view, concluding “that the subject matter of the statuary should be an expression of the ideas, the motivations, the spiritual forces, and the yearnings that have created America.” And with neither of the Samuels alive to say otherwise, the committee supported commissioning architect Paul Cret to create a design “consisting of three terraces with groupings of statues at both ends of each terrace.” The committee decided on sculptural sequences starting with “the early settlement of the eastern seaboard,” “the creation of a nation by the political compacts of 1776 and 1787…and the trek westward.” Figures would embody the “consolidation of democracy and liberty” and represent “the freeing of the slaves and the welcoming to our shores of countless Europeans.” The committee’s plan would bring the story up to the present focusing on “the physical development of man-made America,” and, finally “the spiritual factors that shaped our inner life.”

In January 1933, the Samuel Memorial Committee presented its program at the Fairmount Park Art Association’s annual meeting where it received unanimous approval. Then, “for the ensuing decades,” according to Ingersoll, that plan was “quite closely adhered to.”

In order to cast a wide net and help identify sculptors to populate Cret’s three terraces, the Art Association and the Philadelphia Museum of Art mounted three international sculpture exhibitions in 1933, 1940 and 1949. (Not exactly the donor’s prescribed method, but in a similar vein, the committee believed.) In the first of these exhibitions the public was treated to more than 360 works of art by more than 100 sculptors from around the world. The second exhibition featured more than 430 works. The third exhibition featured more than 250, enabling completion of the Samuel Memorial just after the mid-century.

Did the Memorial deliver on Samuel’s promise to present “statuary emblematic of the history of America”?

“Virtually anyone who has contemplated the Samuel Memorial, even in passing, can sense that there is something unsettling about the choice of sculpture,” wrote Penny Balkin Bach in Public Art in Philadelphia. Instead of achieving Samuel’s mission, the memorial stands as “emblematic of that period of turmoil and transition when artists and patrons were in search of new forms and meanings in an increasingly volatile world.”

[Sources: Penny Balkin Bach, Public Art in Philadelphia. (Philadelphia, Temple University Press: 1992); Dorothy Grafly, “Sculpture at Philadelphia: The Samuel Bequest,” The American Magazine of Art, September 1933, Vol. 26, No. 9 (September 1933); R. Sturgis Ingersoll, “The Ellen Phillips Samuel Memorial,” in Fairmount Park Art Association, Sculpture of a City: Philadelphia’s Treasures in Bronze and Stone (New York: Walker Pub. Co., 1974); Joseph Bunford Samuel, A Word Sketch of Fairmount Park, [Philadelphia: Printed by J. B. Lippincott Company, 1917]; Joseph Bunford Samuel, The Icelander Thorfinn Karlsefini who visited the Western Hemisphere in 1007 (Printed for Private Distribution by J. Bunford Samuel, 1922). News accounts: “Portraits by the Ten Thousand,” The New York Times, November 14, 1896; “An American Portrait Index, The New York Times, March 29, 1902; “Berlin Drive a Great Failure,” The Philadelphia Inquirer, April 26, 1903; “Samuel Estate’s Value is $781,431,” The Philadelphia Inquirer, November 14, 1913; “Model of Park Statues Shown,” The Philadelphia Inquirer, January 30, 1916; “Park to Contain Statue of Viking,” The Philadelphia Inquirer, November 16, 1919; Fairmount Park’s Great Statuary Bequest, The Philadelphia Inquirer, January 15, 1929; “Terrace Statues in Park Finished After 48 Years,” The Philadelphia Inquirer, June 12, 1961.]

Disclosure: The writer is on the board of directors of the Association for Public Art, formerly the Fairmount Park Art Association.

3 replies on “Did the Samuel Memorial Deliver?”

Thanks for this informative note about the beautiful Samuel Memorial on Kelly Drive

I was familiar with the statue of Thorfinn Karlsefini as my wife Lynn Malmgren was the Director of the Swedish Museum in the 1980s, but I never read how he was installed. In fact it was a member of the Board there, who began the Viking Day observations (unrelated to the Museum) at the statue about that time. If you looked into the demise of the statue, you have probably read that a group of supporters of C. Columbus as 1st European in America were responsible for vandalizing the statue and throwing it in the Schuylkill. The Park retrieved and repaired and reinstalled it, only to have it again end up in the drink. The last I heard officials decided to put it in storage. A very sad fate for poor old Thorfinn. As far as I know I am not related to Bunford or Ellen Samuel, though it’s possible. Once about 30 years ago I was interested in finding out more about the Garden, but could not locate any information. I would be very pleased to read more about the Samuel Sculpture Garden.

Thanks for the article.

Ralph David Samuel

Thank you. Some details in the post need to be fact checked.