Once upon a time, sugar was little more than “an exotic spice, [a] medicinal glaze or sweetener for elite palates.” Then slavery changed everything and sugar went global.

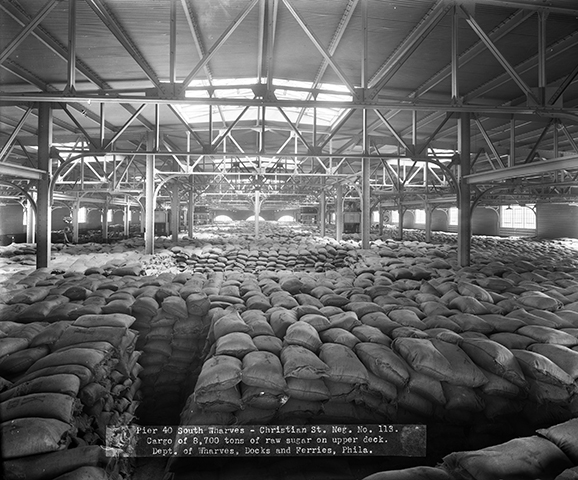

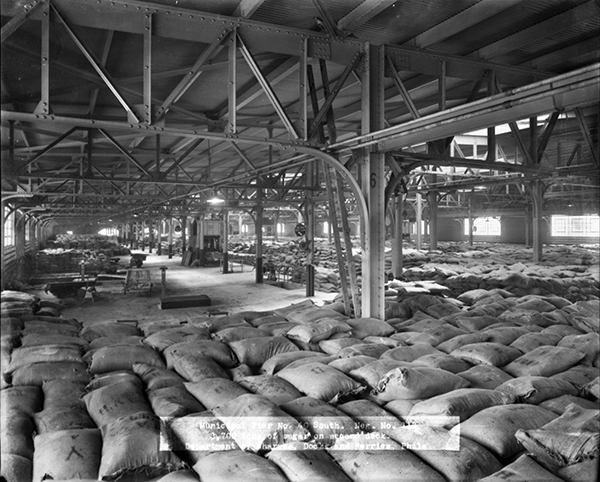

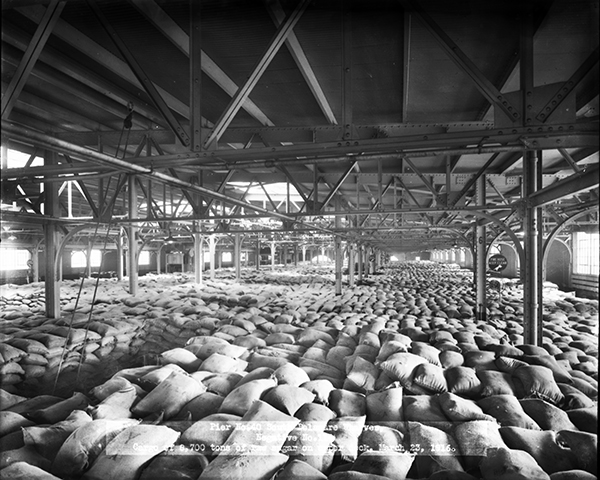

Cane harvested in Cuba, Puerto Rico, and eventually the Philippines and Hawaii was processed into raw sugar, poured into sacks weighing hundreds of pounds each and loaded onto ships bound for America’s urban centers, where refineries produced what came to be known as table sugar.

“Gleaming white crystals would eventually be served in sugar bowls, complete with silver tongs and spoons as part of refined table settings. wrote April Merleaux in Sugar and Civilization. “The ensemble of material goods . . . together with rules for proper use of those items, signified that the eater was fully civilized.”

Refined sugar – superfine and super white – symbolized an elevated social rank, an idea that goes back to the 1870s, when refiners “waged a public campaign to dissuade Americans from eating raw sugar.” We learn from David Singerman’s article, “The Shady History of Big Sugar,” that one advertisement “featured a disgusting insect that supposedly inhabited raw sugar and caused an ailment called ‘grocer’s itch’ in those who handled it.” As racial theorist Ellsworth Huntington put it, we refined sugar “not only to tickle our palates, but to please our eyes by its whiteness.”

“For middle-class people in the United States, writes Merleaux, “to eat refined white sugar was also to internalize a colonial and racial division of labor.” Protected by high tariffs, American sugar refiners enjoyed protections that “maintained the racial hierarchy encoded through the contrast between civilized and uncivilized, technology and nature, refined and raw, white and brown.”

“The government got hooked on sugar, too,” writes Singerman, “by 1880, sugar accounted for a sixth of the federal budget.” And sugar came to play a significant role in government policies. Annexation of Hawaii in 1898 helped guarantee the steady flow of raw sugar to refineries on the mainland. So did a temporary occupation of Cuba and the retention of Puerto Rico and the Philippines as U.S. territories.

At the start of the 20th century, “the American Sugar Refining Company formed as a holding company, and grew into one of the nation’s -largest industrial corporations. According to Merleaux , “sugar refiners were repeatedly the subject of antitrust investigations by the Department of Justice and muckraking journalists.” Indeed, the “Sugar Trust” became “one of the most notorious and successful monopolies of the Gilded Age.”

The City of Philadelphia did what it could to support Big Sugar, including the construction of several state-of-the art piers (including Piers 38 and 40 South) aimed at increasing commerce. Philadelphia’s refineries were able to ramp up production to more than 5.2 million pounds of sugar per day. Philadelphia ranked as the second largest sugar producing city in the world.

So it shouldn’t come as a surprise that while politicians and industrialists were doling out advantages for Big Sugar, physicians and nutritionists were influencing consumers to believe that sugar consumption was, in fact, a “healthy ‘fuel-food,’ necessary to proper nutrition and crucial for people performing heavy labor.” American per capita consumption more than doubled from 32 pounds per year in 1870 to 80 pounds per year in 1910.

“Some years ago,” recalled editors at the Inquirer in 1916, “when the nutritive value of sugar came to be fully realized, an unrestricted use of sweets was advocated in many quarters.… Many mothers were so obsessed with the idea of ‘nutritive value’ that they were inclined to place sugar on a pinnacle, naturally to their children’s delight.” But American sugar consumption had gone too far, claimed the editors, observing that “to a large extent nowadays among the poor classes” mothers are enabling sugar consumption that previously “would have made our mothers’ hair stand on end.”

American sugar consumption remained, then as now, very high, about twice the recommended daily limit. And the reason was more than the appeal of sugar’s sweet taste.

By the 1950s and 1960s, scientists had become aware of links between sugar and obesity, heart disease, diabetes and cancer. But, according to more recent revelations after a deep dive into archival documents, researchers found that the Sugar Research Foundation, a trade group set up to lobby on behalf of sugar, paid Harvard researchers to direct blame away from sugar and aim it specifically toward fat. Their article, published in the prestigious and generally venerable New England Journal of Medicine presented results that “exonerated sugar as a major risk factor for coronary heart disease.”

About the same time Big Sugar was manipulating what was known about the dangers of sugar, this writer was a middle school student in Mr. Donohoe’s history class at Leeds Junior High School in East Mount Airy. After all these years, one specific, ahistorical claim still stands out in memory.

“America is a sugar-eatin’ country,” declared Mr. Donohoe, in class, glowing with national pride.

Couldn’t argue then; can’t argue today. But all these many years later, with real history in hand, the truth has swapped patriotism with cynicism.

[Sources: “Sweets Place Recognized.” The Philadelphia Inquirer, August 5, 1916; April Merleaux, Sugar and Civilization: American Empire and the Cultural Politics of Sweetness (University of North Carolina Press: 2015); Kearns, Cristin E et al. “Sugar Industry and Coronary Heart Disease Research: A Historical Analysis of Internal Industry Documents.” JAMA internal medicine vol. 176,11 (2016): 1680-1685; Anahad O’Connor, “How the Sugar Industry Shifted Blame to Fat,” The New York Times, September, 12, 2016; David Singerman, “The Shady History of Big Sugar,” The New York Times, September 16, 2016; Khalil Gibran Muhammad, “The Sugar that Saturates the American Diet has a Barbaric History as the ‘White Gold’ that Fueled Slavery,” The New York Times, August, 14, 2019]

3 replies on “The Rise of Big Sugar”

Another amazing article about how market forces influence political and cultural pressure in the US of A. Thanks, Mr. Finkel, for continuously informing me of the ways of the past, and present

Thanks, Mr. Finkel, for once again enlightening me of how market forces influence political and cultural pressure, yesterday and today.

The history of Big Sugar is indeed fascinating as I learned while researching my biography of Charles Hires, Philly’s root beer king. For example, Hires followed Milton Hershey’s lead by purchasing a Cuban sugar plantation and mill in 1919. They sought protection from shortages and wild price swings that whipsawed sugar-dependent businesses during World War I and its aftermath. Fortunately for Hires, the company managed to unload its Cuban holdings a few years before Fidel Castro nationalized U.S. businesses there.