In 2008, three men made a pilgrimage from Philadelphia to Frisby’s Prime Choice plantation in Cecil County, Maryland. The first was Phillip Seitz, curator of the Cliveden estate, a National Trust historic site in Germantown and the long-time home of the Chew family. The second was John T. Chew Jr., a member of Cliveden’s board and a descendant of the original owner. The third was John Reese, chef and former employee at Cliveden, who is captivated by the untold stories of those who lived and worked at the estate.

What prompted their visit were discoveries in the Chew family papers, recently archived by the Historical Society of Pennsylvania. These documents not only provide a rich record of seven generations of one of Philadelphia’s most eminent legal families, but also names and descriptions of the slaves that worked the various Chew plantations two centuries ago.

After driving through endless fields of wheat, Reese asked if they were getting close to Frisby’s Prime Choice. Seitz responded that they had been driving through the former Chew plantation for the past 20 minutes. According to Chew family records, about seventy enslaved African-Americans farmed over 1,000 acres of land during the late 18th century.

After visiting the plantation house, they drove 40 minutes due east to the river landing, where two hundred years ago, the slaves loaded the produce they harvested by hand onto waiting ships.

As he stood on the river bank, Reese was convinced he could see ghosts of these men rolling barrels down to the dock.

Chew was deeply moved as he watched Reese tear up. “When I saw John visibly moved, looking out over fields of long grass, stretching to the horizon,” he remembered, “I was overcome with a deep sadness for enslaved people, and their plight. John – and the moment – helped me feel in a way I never had before the sorrow, the anger, and the frustration of people held against their will.”

* * * *

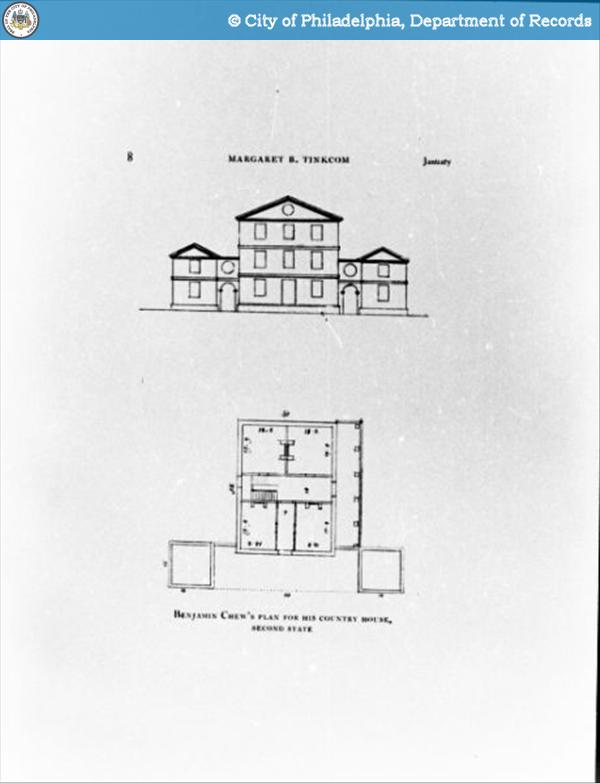

Early sketch of plans for Cliveden c.1760, possibly drawn

by master carpenter Jacob Knor and Benjamin Chew.Cliveden’s original owner, Benjamin Chew (1722-1810), was the son of Maryland Quakers. He received his training in London’s Middle Temple, making him one of the most highly-trained lawyers in the Colonies. The Penn family recognized his talent, and he became their principal legal advisor. Unlike other lawyers of the time, who had a penchant for flowery and wordy opinions, Chew’s writing was defined by brevity and clarity.[i] Chew’s crowning appointment was Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of the Province of Pennsylvania – he was the last man to hold that position before America declared independence from Great Britain. In addition to his legal prowess, Chew was a shrewd land speculator. Much of the wealth that supported the family’s lavish Philadelphia lifestyle flowed from several tobacco and wheat plantations in Maryland and Delaware.

In 1767, Benjamin Chew completed a summer retreat in Germantown he called Cliveden, built in the highest Georgian style. The estate had manicured gardens, wooded groves, and several outbuildings, including a large carriage house. The inside of the stone mansion boasted elaborate woodwork and furnishings imported from England. Although he possessed no architectural training, it appears that Chew had a hand in designing the house.

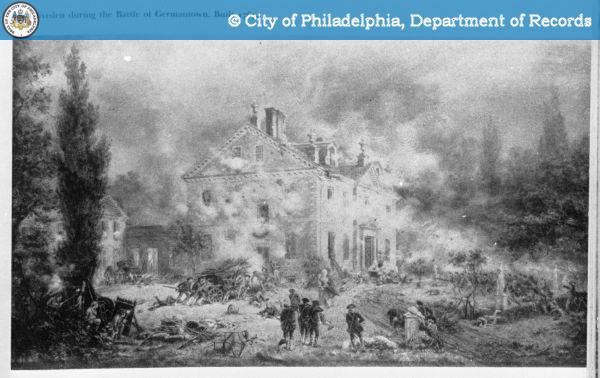

Cliveden under assault by Washington’s troops

during the Battle of Germantown, 1777.During the American Revolution, the pacifist Chew sided with the Crown and his principal clients, the Penn family. As a result, the Continental Congress placed him under house arrest in New Jersey. After the Revolution, Chew returned to his successful legal practice. Despite questions about his loyalty, George Washington and John Adams had immense respect for him, and friendships such as these allowed Chew to reclaim his position in the Philadelphia power structure. Back on his feet, Chew repurchased and restored his beloved summer house, badly damaged by artillery fire during the 1777 Battle of Germantown.

The Chews continued to own Cliveden until 1972, when they donated the house and its contents to the National Trust for Historic Preservation. Today, the house is filled with antiques and family heirlooms, some dating all the way back to the time of Benjamin Chew. But hidden away in Cliveden’s nooks and crannies were thousands of pages of letters, journals, account books, and other correspondence that the family maintained over the past two centuries. Like the Adamses of Massachusetts, the Chews kept everything they wrote, making the collection a boon for American historians. These documents brought the human story of the Chews back to life — they mourned the deaths of loved ones, squabbled over inheritances, and kept track of their expenditures.

The papers also revealed in vivid detail about how much of the Chew’s early wealth had come from slavery. Correspondence between the Chews and their overseers demonstrated that the slaves on their plantations were far from compliant. During the Revolution, when Benjamin Chew was briefly imprisoned, a number of his slaves ran away. Those that remained on the plantations developed their own unwritten social and work rules. One time, the overseer at one of these plantations wrote Benjamin Chew pleading for back-up. Two slaves named Aaron and Jim had badly beaten him after his brutal treatment of the work force during the harvest season. It took three weeks for Chew to send reinforcements and bring order to the plantation. Aaron and Jim submitted to the whipping, sacrificing themselves for the good of their fellow slaves.

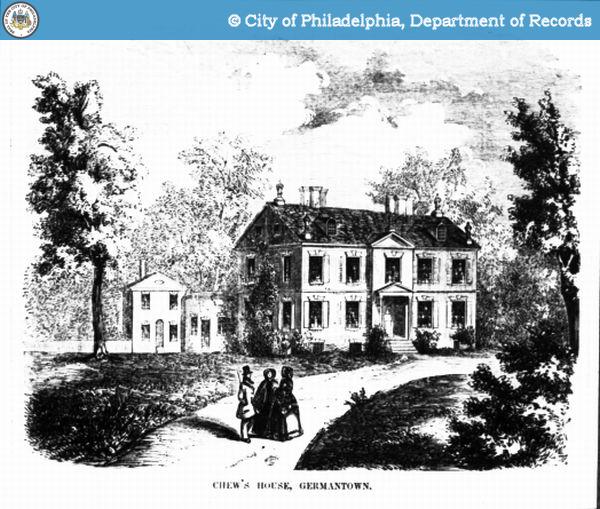

Illustration of Cliveden c.1850.After the American Revolution, Pennsylvania abolished slavery, but the Chews continued to hold onto their properties in the slave states of Maryland and Delaware. But by the early nineteenth century, the Chews saw the writing on the wall. They decided to divest themselves of their family plantations and put their capital in Pennsylvania industry and land speculation. Benjamin Jr., who served as his father’s principal plantation manager, was put in charge of this task for his extended family. In 1809, Benjamin Jr. traveled south to settle the estate of an uncle who had died in debt. In his letters home, he was clearly torn between family financial obligation and the fate of his uncle’s slaves, who had been denied the freedom their master had promised them.

“I found it absolutely necessary to return to this Place which I did last Evening and tomorrow sell off the Remains of any poor Uncle John’s Remnants,” Benjamin Jr. wrote his father on November 15, 1809. “I have fortunately succeeded in providing Homes for all but 7 or 8 of the Black People—a Task indeed of the most conflicting Difficulty—I have I believe succeeded in giving the poor Creatures as much Satisfaction as they could have, under a disappointment in not having their Freedom bequeathed to them—they generally thank me for what I have done for them—the Stock of all kinds I have also sold except what is necessary to retain to secure the Crops.”[ii]

* * * *

The Chew family papers — donated by the family to the Historical Society of Pennsylvania in 1982 — were opened to the public last year. A grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities paid for the meticulous archiving and conservation process. At the opening ceremony on October 14, 2009, representatives from N’COBRA (National Coalition of Blacks for Reparations in America) demanded that the legacy of slavery play a prominent role in shaping the presentation of these documents. The meeting at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania at times grew heated. According to the N’COBRA website, “reparations are needed to repair the wrongs, injury, and damage done to us by the US federal and State governments, their agents, and representatives.”[iii]

As a result of discoveries in the papers, Cliveden found itself in the public spotlight. Those interested in the future of Cliveden—people like Phillip Seitz, John Reese, and John T. Chew Jr.—decided the best approach was to face the controversy head-on. It also could be an opportunity to revitalize what had previously been a rather traditional house museum that focused on the lives of its wealthy occupants.

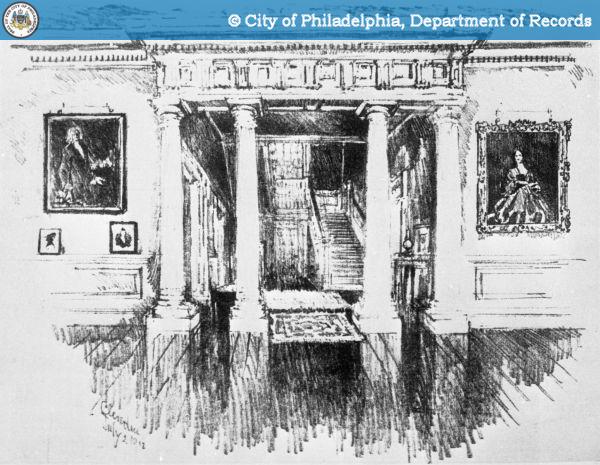

Artist’s sketch of the Main Hall.“Cliveden was not afraid to face what the papers reveal,” curator Phillip Seitz said. “What we realized was that the grandeur of Cliveden was the very top layer of a very complex onion, an onion that needed to be peeled back.”

Since the release of the Chew family papers, Cliveden’s management has engaged the surrounding community in a number of meetings and dialogues. This past fall, Cliveden sponsored a series of four well-attended lectures entitled “Cliveden Conversations” in the former carriage house. Speakers included Phillip Seitz, who discussed the Chew family’s involvement with slavery; Dr. Erica Dunbar-Armstrong of the University of Delaware, who gave a broad overview of slavery in the Mid-Atlantic region from a woman studies perspective; Ari Merretazon of N’COBRA, who discussed his organization’s goal of reparations for the descendants of slaves; and Dr. David Young, Cliveden’s executive director, who framed the house in the context of 20th century race relations in Germantown.[iv]

Cliveden’s management hopes not only to bring about racial healing, but to more fully integrate their house museum into the predominately African-American Germantown neighborhood, making themselves “a catalyst for preserving and reusing historic buildings to sustain economic development for historic Northwest Philadelphia and beyond.”[v]

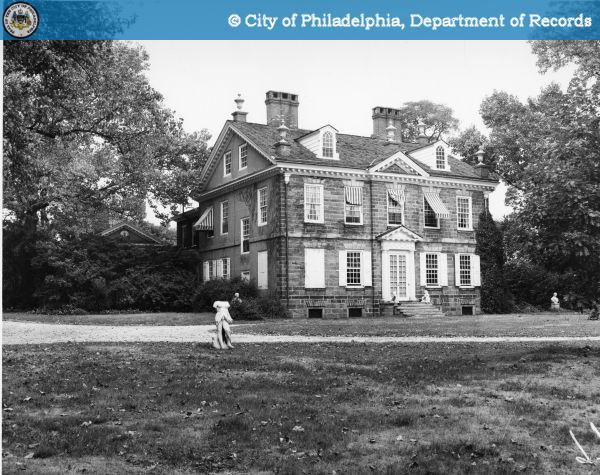

Photograph of Cliveden, 1957. The Chew family owned the

mansion until 1972.“We are giving people what they want,” Seitz said. “They don’t want more exhibits. They want story tellers, news articles, and they need affirmation that things happened here…not just bad stories, but also stories of survival.”

John Reese agreed. “Let’s have the courage to confront this.” For his part, Reese sees Cliveden in a positive light, now that a more complete story is being told. Exploring the house’s history was also a catalyst for friendships with curator Phillip Seitz and board member John Chew Jr.

“I love the house,” Reese said, sitting on a picnic table in the shadow of the craggy stone mansion. “That banister in the main staircase is solid as a rock. You look at how flimsy houses are today, and I have a hard time ever seeing Cliveden getting blown down.”

Special thanks to Philip Seitz, John Reese, and John T. Chew Jr. for their time and insights. The interviews were conducted on October 8, 2010 at Cliveden.

[i] “Legends of the Bar,” The Philadelphia Bar Association. http://www.philadelphiabar.org/page/AboutLegends?appNum=4 Accessed October 18, 2010.

[ii] Benjamin Chew Jr. to Benjamin Chew Sr., November 15, 1809. The Chew Family Papers, Historical Society of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. http://www2.hsp.org/collections/manuscripts/c/Chew2050.xml#series2 Accessed October 16, 2010.

[iii] “N’COBRA Information” http://www.ncobra.com/ncobra_info.htm Accessed October 18, 2010.

[iv] ‘Cliveden Conversations,” Cliveden: A National Trust Historic Site in Philadelphia.” http://cliveden1767.wordpress.com/visiting-cliveden/calendar-of-events/ Accessed October 18, 2010.

[v] “Mission Statement,” Cliveden: A National Trust Historic Site in Philadelphia.” http://cliveden1767.wordpress.com/mission-statement/ Accessed October 18, 2010.