Philadelphia’s Delaware River waterfront has played a significant role in the city’s development ever since William Penn himself stepped foot on the area we now call, rather appropriately, Penn’s Landing. Penn’s oft-mentioned plan for Philadelphia as a “greene country towne” included a tree-line waterfront that would serve as a serene promenade for Philadelphians to come and relax. However, the waterfront quickly become the economic and commercial heart of the young city, with the Delaware River serving as a major highway for the importing and exporting of goods from the European continent. Penn’s idea of serenity quickly gave way to the hustle and bustle of a rapidly expanding city. As the city grew, shops, warehouses, and factories continued to cluster along the waterfront, and with the advent of the railroad in the mid-19th century, the area become further congested with tracks leading from the docks, piers, and warehouses into the interior of the country.

For the first centuries of the nation’s life, Philadelphia was considered by many to be its most major port. However, by the early-20th century, Philadelphia’s port infrastructure was showing its age, and Philadelphia had clearly been surpassed in importance by ports in cities like New York City, Boston, and Baltimore. In 1907, the City of Philadelphia created the Department of Wharves, Docks, and Ferries and tasked it with rejuvenating the waterfront area and making it once again a competitive port for international trade and commerce. This long-term plan included the dredging of the Delaware River channel from the sea to Allegheny Avenue to a depth of 35 feet to handle larger ships, the construction of the Delaware River Bridge (now called the Benjamin Franklin Bridge), and the construction of several new, municipally-owned piers to be leased out to private companies. The entire project took two decades to be fully realized and cost an extraordinary (for the time) $27,000,000.

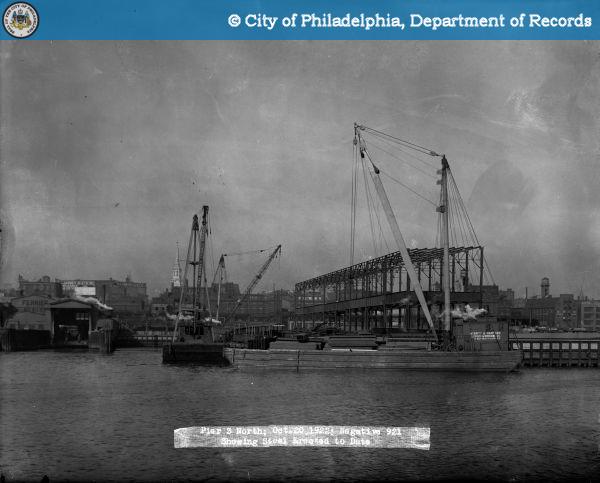

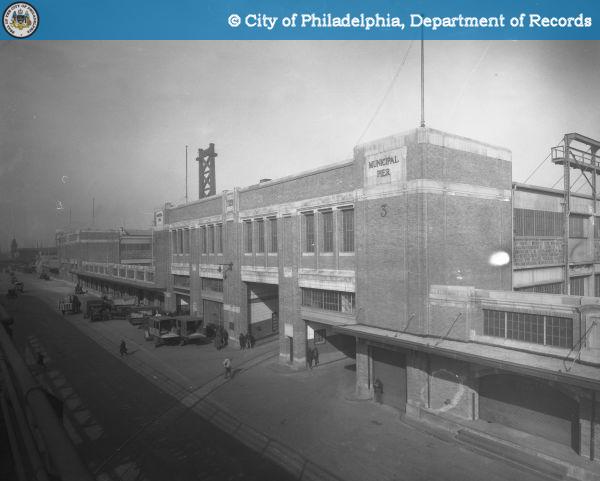

One of the last components of the project was the construction of Piers 3 and 5 North in 1922-23. These two new piers were constructed on the site of several aging wooden wharves built in the 19th century with money that had been left to the city by Stephen Girard. Therefore, the piers were officially called the “New Girard Group”, though they came to unofficially be known as just the “Girard Group” or the “Girard Piers.” These double deck piers were designed with all the latest technological advances of the time in order to increase efficiency and handle the maximum amount of cargo in one day. They extended 550 feet into the river, the maximum amount allowed by the federal government to maintain safe navigation of ships through the channel, and could therefore service more than one ship at a time. “Turn over” doors that folded upward and inward ran along the entire length of each side of the piers and allowed for the loading or unloading of cargo from a ship’s deck from any point along the pier. Each pier had about 100,000 square feet of storage space and also contained office space on both the upper and lower decks for the companies who would lease the piers. Finally, each pier had an automatic sprinkler system installed that was connected to the city’s water system.

While the steel-framed sides of the piers were certainly utilitarian in their appearance, the inshore and outshore steel frames were encased in brick and limestone and were designed with utmost care by John Penn Brock Sinkler, City Architect from 1920-1924. The embellished facades belied the piers’ strictly industrial use, and at the time they stood in stark contrast to the plainness of normal pier design. The Girard Group’s blend of state-of-the art functionality with architectural expression was said to have ushered in a “new interpretation of industrial architecture.”

Despite all of their technological advancements, the Girard Group piers were rendered obsolete after World War II with the construction of newer port facilities in South Philadelphia and changes in methods of cargo handling, particularly the rise of containerization. The Delaware waterfront industry in general began to suffer in the 1950s and 1960s as companies moved to markets with cheaper labor. Demolition of many waterfront factories and warehouses in order to construct Interstate-95 in the late 1960s delivered a final crushing blow. The Girard Group, once a source of great pride for the city, sat derelict and decrepit.

As Philadelphia began to plan for the country’s bicentennial, city planners sought to finally realize William Penn’s vision of a tree-lined promenade along the waterfront. Called Penn’s Landing, the Girard Group were marked for demolition to make way for this park. However, like other large-scale city projects, only half of Penn’s Landing was finished in time for the bicentennial, thereby sparing the Girard Group. In 1983 the Girard Group were added to the National Register of Historic Places and were renovated as luxury condominiums. Renamed “The Piers at Penn’s Landing,” the luxury condo conversion struggled at first, but by the 1990s they were successfully established luxury condominiums. The turn-over doors once used for loading and unloading cargo became large picture windows, the railroad entry and loading depot on the ground floor became a parking garage, the roofs of both piers were removed creating a sun-drenched atrium for residents in the center of each pier, and a marina full of recreational boats rather than cargo ships now surrounds the piers.

This blending of the past with the present, with taking something old and repurposing it into something new, is something that seems to occur often in Philadelphia. The Girard Group/The Piers at Penn’s Landing stand as testaments to how adaptive reuse, plus a little patience, can further add to the rich historical story for which Philadelphia is known.

Resources:

Kyriakodis, Harry. “The History of Pier 3.” http://www.pier3.net/history_of_pier_3.

“Piers 3 and 5 North (The Girard Group), 1923.” http://www.workshopoftheworld.com/center_city/pier_3.html.

“Penn’s Landing – William Penn’s “Greene Country Towne” has Finally Become a Reality Here.” http://www.ushistory.org/tour/penns-landing.htm.