[Note: In light of this past week’s actions at the President’s House, this post reveals a fuller history of the site and its connections to slavery.]

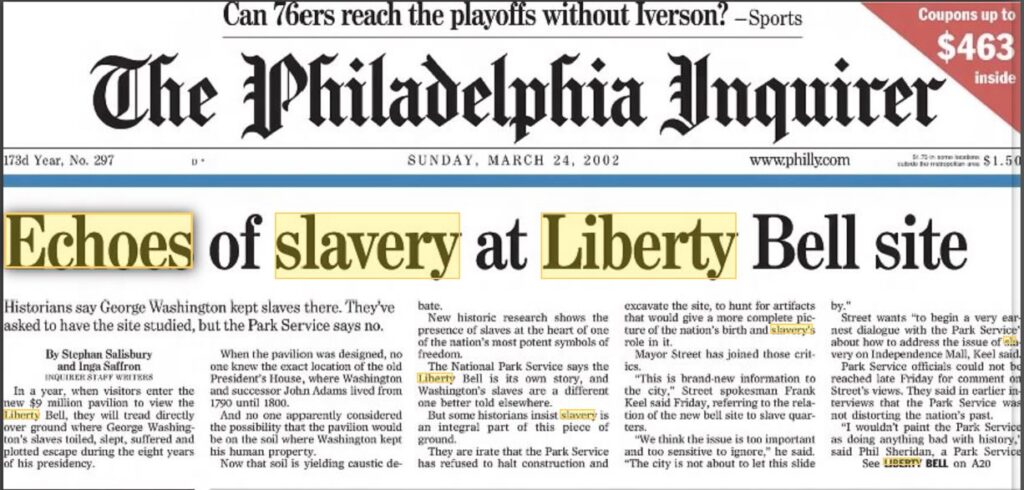

On March 24, 2002 a page-one, above-the-fold story by Stephan Salisbury and Inga Saffron broke the news: No one, most especially the designers of the new Liberty Bell pavilion, had “considered the possibility that the pavilion would be on the soil where Washington kept his human property.” According to the Inquirer, “new historical research show[ed] the presence of slaves at the heart of one of the nation’s most potent symbols of freedom.”

And yet, as historian Gary Nash had pointed out to Marty Moss-Coane, in a WHYY RadioTimes interview a few months earlier, the National Park Service (NPS) chose to “perpetuate the historical amnesia about the founding fathers and slavery.’’ Many scholars, advocates and others felt strongly that “the story of slavery was an integral part of this piece of ground.”

The Inquirer article, followed by an editorial a few days later, argued that “the Liberty Bell in its new home must not bury an ugly part of the country’s history.” The National Park Service disagreed.

These articles were the first of what amounted to an avalanche of advocacy and media – articles, editorials and programs – that would be collected and shared online by the non-profit Independence Hall Association. Also essential was the work of ATAC (Avenging The Ancestors Coalition), founded in 2002 to compel the National Park Service and Independence National Historical Park “to finally agree to the creation of a prominent Slavery Memorial” at the President’s House project. More on these resource-rich websites here, here and here.

Over time, a new and more inclusive narrative emerged, proved popular and was embraced by the Park Service. The Park Service also conducted its own research, which included a substantial archeological dig. This was shared with an increasingly interested public that visited the temporary platform at the site. As Stephan Salisbury put it, this plain wooden platform was transformed into “a historic platform for dialogue on race.”

According to NPS archeologist Jed Levin, the dig led to a “surprising series of discoveries and a stunning outpouring of public interest.”

According to Levin: “As intended, on that platform visitors observed the progress of the dig and listened to members of the archeological team talk about what we were uncovering and about slavery and freedom in early America. But almost from the start visitors to the platform engaged with the archeologists—and with each other—in passionate exchanges alternately punctuated by anger, tears, and sometimes even joy.”

By the time work was completed at the end of July, more than a quarter of a million people visited the “simple wooden viewing platform… overlooking the excavation.”

Source: Jed Levin, “Activism Leads to Excavation: The Power of Place and the Power of the People at the President’s House in Philadelphia,” Archaeologies: Journal of the World Archaeological Congress (2011).

One reply on “The Power of the President’s House”

Thanks for reminding us all Ken.