German immigrants gathered en masse (or massenhaft?) to celebrate their readymade music culture. In 1835, Philipp Mattias Wolsieffer, a German-born music teacher, launched the Philadelphia Männerchor, the first German-American singing society, with a three-day festival. A parade headed by a brass band led 400 singers to Independence Square, where, in addition to the Teutonic classics, they pleased the audience of 10,000 with Hail, Columbia and The Star Spangled Banner. No venue in the city – not even Washington Hall near 3rd and Spruce (which had room for 6,000) – could host events on such a scale. And so it was for the balance of the 19th century, as choral groups and musical societies and their audiences expanded, while the venues that could host them did not.

Singers, their families, plus older and newer German arrivals gathered in streets and public squares to share music, lager, pretzels, sausages, folk dances and political speeches. During these traditional German-American Saengerfests, flags and banners filled the streets, bands played for day-long picnics and singers performed for ever expanding audiences.

Massive indoor performances were out of the question until 1897, when the 18th National Saengerfest came to Philadelphia.

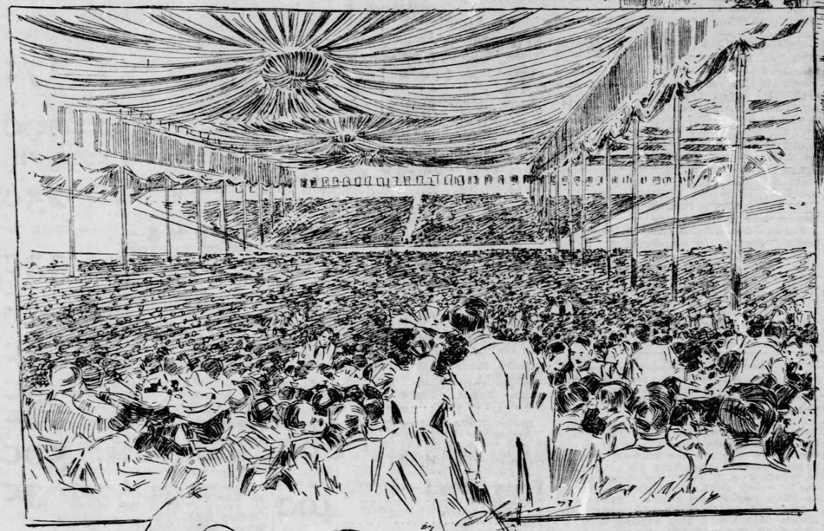

Finally, in 1897, the lack of a venue for large numbers of performers and audiences, was dealt with by building a giant, if temporary, hall on Fotterall Square in North Philadelphia. This structure accommodated a full orchestra, 6,000 singers and an audience of 8,000. Fifteen years later, in 1912, when Philadelphia hosted the 23rd National Saengerfest, even more ambitious plans called for a permanent hall twice as large, though at a cost far beyond the capabilities of Philadelphia’s musical organizations.

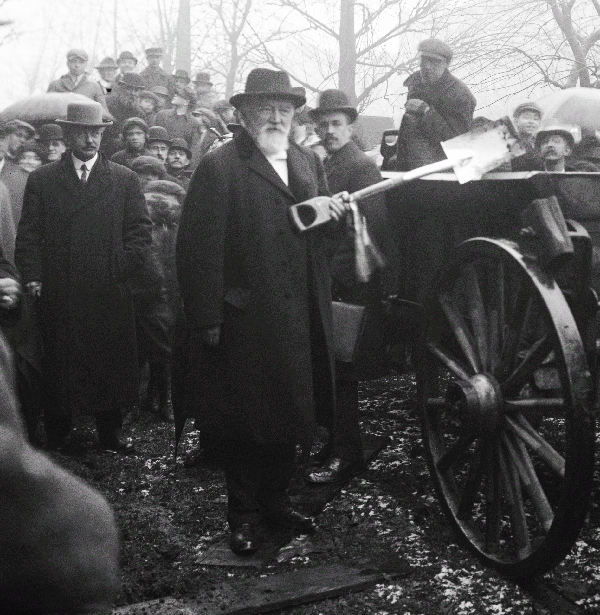

Realizing the need for a permanent convention hall, city officials considered a variety of locations and allocated funds for design and construction. But there simply wasn’t enough time to build and outfit a large, permanent venue. Some even worried that a temporary venue might not be ready in time. To assuage doubt, Philadelphia’s newly-elected mayor, the German-born Rudolph Blankenburg, got behind the idea of a temporary hall. He attended the annual reunion of the United Singers of Philadelphia held at Harmonie Hall, accepted the title of the Saengerfest’s honorary president and reiterated his promise to deliver a hall on time. To manage this, Blankenberg paved the way for an expedited commission from architect Carl P. Berger and convinced City Councils to waive “laws governing the erection of framed buildings.”

On February 26th 1912, with only 124 days to the start of the Saengerfest, Blankenburg broke ground in ceremonial fashion at Broad Street and Allegheny Avenue. The completed hall would be 265 by 408 feet. Its main floor would accommodate audiences of 8,555 in addition to 6,000 singers on a raised stage. A giant, U-shaped balcony seated another 4,746. The total capacity of the hall: an impressive 19,301. The structure of columns, trusses and girders – all fashioned of wood – guaranteed a quick turnaround for the project. But even then, progress was dicey. On May 14th, a mere 76 days before opening, a city photographer documented a structure that was only half-built.

At 8 PM on Saturday, June 29th, the hall’s first concert, powered by a full orchestra and 2,000 voices, got the festivities off to a roaring start. The nine-part program started with the orchestral prelude of Richard Wagner’s Meistersinger followed by the men’s chorus performing Wilhelm Speidel’s Viking Expedition. Then came the women’s chorus performing Edward Elgar’s The Snow. The evening concluded with the finale of the first act from Felix Mendelsohn’s unfinished opera, Lorelei.

The Saengerfest’s second day continued with a Grand Children’s Concert of 6,000 Public School students prefaced by the orchestra performing Rossini’s William Tell Overture. Then everyone took part in John Hatton’s O God Beneath Thy Guiding Hand. Other pieces included works by Wagner, Donizetti, Rossini and Mendelsohn, concluding with Henry T. Gilbert’s Thunder Maker with the voices of 2,000 grammar schoolboys. The final piece was Watch on the Rhine, the German National Hymn.

The complete Saengerfest program went on for five days.

In subsequent years, the hall found uses for a range of events, from the National Baptist Convention to a Wild West Show, an automobile display, an “Athletic Carnival” and a “Summer Garden” complete with vaudeville theater.

Meanwhile, the building’s vulnerability to fire grew worrisome. “Convention Hall Called Fire Trap” read a headline only a week after the Saengerfest. A prominent insurance executive suggested that letting the building remain standing would be “a menace to lives and property,” the equivalent of storing a powder kegs and dynamite in the basement of City Hall. What could possibly go wrong?

Four years later, in October 1916, the official order came down: stop using Convention Hall. Demolish it.

Convention Hall avoided its anticipated conflagration. And the public debate about a new, permanent hall – this time fireproof – continued with renewed intensity.

(Sources: Heike Bungert, “The Singing Festivals of German Americans, 1849–1914,” American Music, Vol. No 2, Summer 2016, pp. 141-179. Jeff Wiltse, “Cities are Alive with the Sound of Music: Saengerfest and the Transformation of Urban Public Music in Nineteenth-century America,” American Nineteenth Century History, 2015, 16:3, 269-296. Twenty-third National Saengerfest, Official Souvenir Program: Nord-Oestliche Saengerbund of America (Philadelphia, June 29th to July 4th, 1912) Published by the National Saengerfest of the Northeastern Saengerbund. (Philadelphia, 1912). In The Philadelphia Inquirer: “Mayor to Name Site for Hall Tomorrow,” Jan. 4, 1912; “Ready To Locate Convention Hall, Jan. 6, 1912; “City Will Erect Convention Hall on Broad St. Site, Jan. 9, 1912; “Convention Hall Plan Completed, Jan 28, 1912; “$50,000 for Hall is Recommended,” Feb, 2, 1912; “Mayor Begins Work on Convention Hall Convention Hall,” Feb. 27, 1912; “Convention Hall Schedules Filed,” Apr. 2, 1912; “Famous Soloists Will Lead Great Festival of Song,” June 16, 1912; “Convention Hall Soon to be Musicians Mecca,” June 23, 1912; “Chorus of 2000 Open Festivals of Song Tonight,” June 29, 1912; “Convention Hall Called Fire Trap,” July 11, 1912; “Mayor to Build Permanent Hall For Conventions, July 22, 1912; “Wild West and Far East Show to Open,” April 3, 1913; “Meadowbrook Athletic Carnival Tonight,” Feb. 21, 1914; “Movies in Convention Hall,” May 23, 1914; “Vaudeville at Convention Hall,” May 28, 1914; “A Genuine Novelty,” June 23, 1914; “New Designs at Automobile Show,” Dec. 12, 1915; “To Raze Convention Hall,” May 18, 1916).

One reply on “The Rise and Fall of a Convention Hall”

Thanks for clearing up that mystery. Less than 5 years after being built, it was gone? I knew it was there because it had a fire alarm box associated with it (2335, a new box, per the number, at “Broad and Allegheny, Convention Hall”, the box later moved to Tulip and Rhawn in the Northeast) but the 1925 Bromley map shows “Ford Motors” at that location. That was a lot of lumber and money for a short duration. And I thought it was bad that they tore down the U of P area Convention Hall after70 years.