Rudolph Blankenburg had long been committed to civic improvement and reform politics in Philadelphia, a city better known as corrupt and content. He won the election for county commissioner in 1905 and the mayor’s office six years after that, promising to fight entrenched Republican corruption. Blankenburg served one term as mayor, from December 1911 to January 1916.

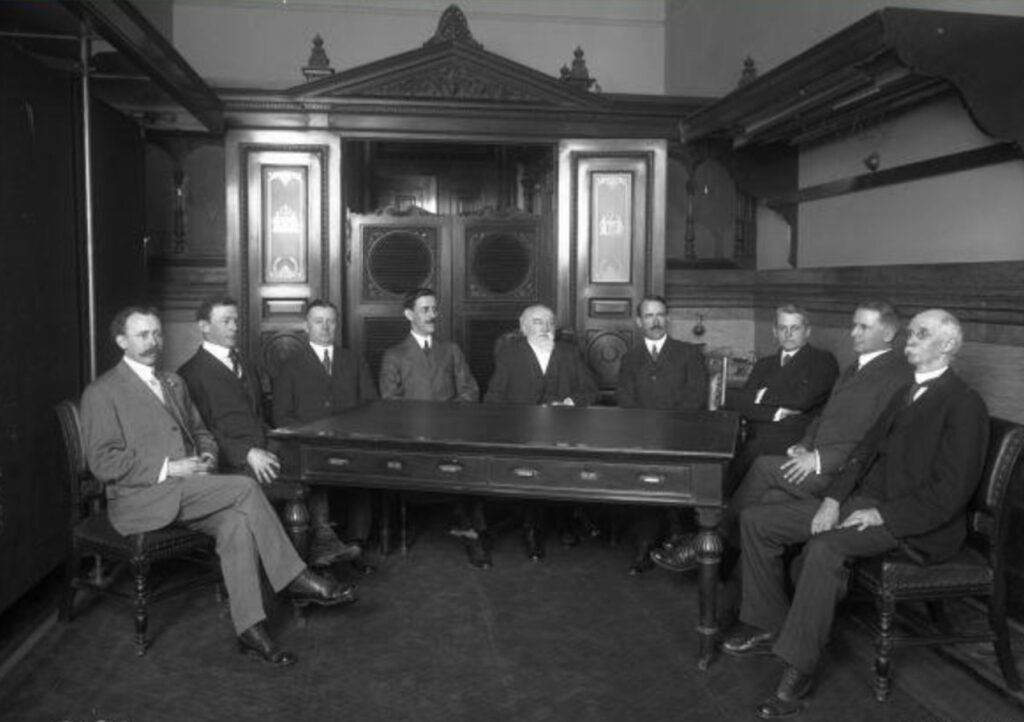

With “The Dutch Cleanser,” as his nickname, Blankenburg learned to use public relations tools that would distinguish his administration. Photography was one of those tools. We can only imagine his frustrated reaction when shown the picture of his cabinet sitting around a conference table. It evoked a degree of earnest Quakerly competence, but entirely lacked anything resembling spark, or as some later mayors might have called it, pizzazz.

How might a can-do mayor, backed by a uniquely honest administration, put the medium of photography to better use? Could an image communicate progress and reform? That was the challenge.

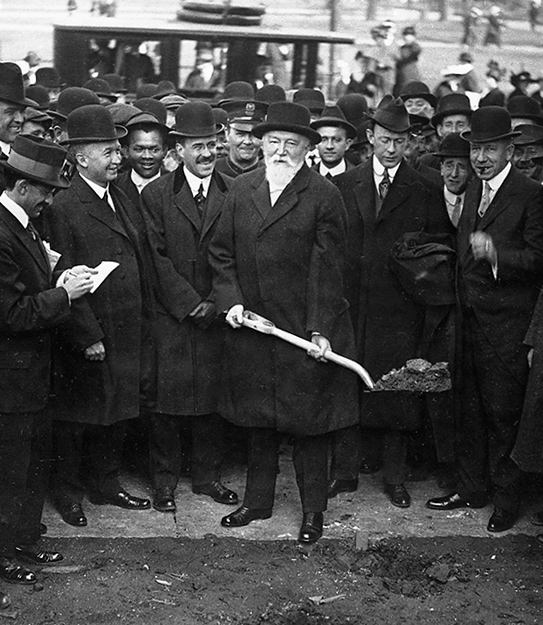

Shortly after Blankenburg’s election the city broke ground at Broad and Allegheny for a gigantic new civic space. This new Convention Hall would accommodate audiences of more than 19,000 with a stage that could be packed with 300. The mayor turned out for the groundbreaking festivities with his shovel and a city photographer and turned what might have been a mundane moment into a growing genre of civic imagery, one that Blankenburg would revisit again and again over his years in office. Where a broom might be an apt symbol for “The Dutch Cleanser,” a shovel would become his second favorite prop. This this black-suited, white-bearded mayor needed no convincing to grab his ceremonial shovel and leave City Hall. Blankenburg had mastered the photo-op.

And as he and his entourage got better at deploying their public relations skills, the Press took notice. Not only would they report on the gesture of breaking ground but also on the banter among with political friends and foes who would inevitably, predictably, want a piece of center stage. The most inevitable and predictable rival was state Senator James P. “Sunny Jim” McNichol, a “top Republican potentate.” McNichol’s construction companies had him literally running half the city. His Filbert Paving and Construction Company, took in $3 million between 1903 and 1911. His Penn Reduction Company, a garbage-collection enterprise, had annual contracts exceeding $500,000. “And his Keystone State Construction Company handled contracts for the Market Street Subway, the Torresdale water filtration plant, and the Northeast Boulevard.” The groundbreaking at 19th and the Parkway – a project that would complete the transformation of the square into a circle – was a mere $151,000, but it all added up.

The mayor and “Sunny Jim,” attacked each other verbally as they wielded their shovels. The senator “tossed bantering remarks back and forth,” reported the Inquirer. The mayor, “encouraged by the good-natured joshing of Senator McNichol, drove a spade deep into the ground and turned the first shovelful of dirt on the new contract. Advised by Senator McNichol that he was making fine progress, [Blankenburg] promptly repeated the performance.” Then “Senator McNichol removed a spade full of dirt, while about one hundred and fifty of his laborers grinned at the spectacle.” Finally, the mayor and his nemesis “clasped hands . . . and posed for newspaper photographers.”

And then they exchanged more unscripted words. “’I have a better grip than you, Senator,” said the mayor suggesting that he had more manly strength. “Right back came McNichol’s reply McNichol: ‘That may be, but the trouble is that you are losing yours while mine is just coming.’”

“Oh no, I have still a good grip,” said the mayor, “I am on the firing line and will continue to be there…”

In the final months of his term, Blankenburg launched what was considered “the greatest project in the history of the municipality” – the Broad Street Subway. At that groundbreaking, the mayor “turned a shovel of earth” at the northwest corner of City Hall Plaza, “and started Philadelphia on the way to its long-looked–for high-speed transit facilities.”

“We are making history here today,” declared the mayor at the groundbreaking, “this great engineering work . . . marks the beginning of a new era in the life of Philadelphia.” After the speeches came the shovels and finally the banter. The mayor “stepped forward, put his heel to the shovel and posed for photographers and moving picture operators.” After a few rounds with the shovel one of the participating officials spoke out: “Mr. Mayor, you are doing all the work. Let Senator McNichol do some.” The mayor chuckled and replied: “Never mind about Senator McNichol. He’s the fellow who will get the money for my work.”

Groundbreakings as joking photo-ops grew more frequent over the years. Sure, there were the usual speeches and shovels. There was also a somewhat clownish reinterpretation at the start of demolition for a 1000-car parking garage for a pair of ill-fated department stores at Market East. Here, the shovel wasn’t enough. What would be? A white bulldozer, seemingly “dressed” for the occasion.

Dressing for the occasion meant something. At yet another groundbreaking that same year, a trio of uniformed Hahnemann nurses posed with lipstick while “prettying up” with the help of a mirror-polished, silver-plated, ceremonial shovel.

And the Press seemed to very much like that twist on the old photo-op idea.

(Sources: Francesca Russello Ammon, Bulldozer: Demolition and Clearance of the Postwar Landscape (Yale University Press, 2016); Donald W. Disbrow, “Reform in Philadelphia Under Mayor Blankenburg, 1912-1916.” Pennsylvania History: A Journal of Mid-Atlantic Studies 27, no. 4 (October 1960); John Hepp, “Subways and Elevated Lines,”The Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia; Thomas H. Keels, “Contractor Bosses (1880s to 1930s),” Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia.

In The Philadelphia Inquirer: “Mayor Wields Shovel to Inaugurate Work for Real Rapid Transit,” and “Cheers Ring Out as Mayor Starts Work for Transit,” March 21, 1915; “Final Parkway Work is Begun,” and “Mayor Uses Spade on Parkway Section,” April 13, 1915; “To Break Ground September 11 for Broad Street Subway,” August 29, 1915; “Mayor Launches Work on Subway as Crowd Cheers,” September 12, 1915; “1000-car Garage to be Built at Lits and Strawbridges,” March 2, 1962; “Rites Will Mark Start of Garage,” November 22, 1962; “Work Started on Nurse Home For Hahnemann,” June 7, 1962.)