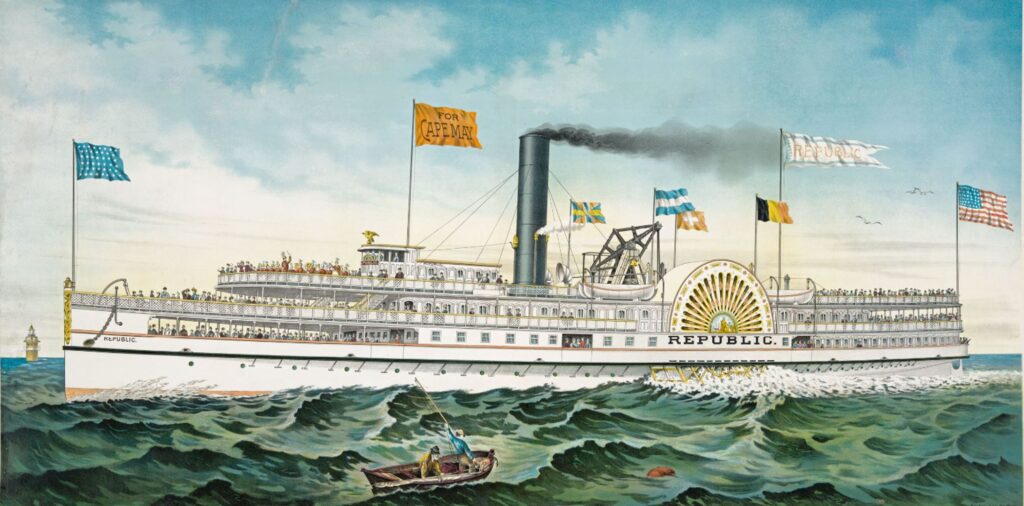

A July 1879 Inquirer advertisement promoted “the A1 Mammoth, three deck palace iron steamship Republic” which leaves “the Race Street wharf every day at 7:15 AM returning from Cape May at 3:00 PM arriving in city early in the evening.” On board, “a band of music will accompany the boat and a variety of pleasant and amusing entertainments will be given during the passage.” The year-old steamer had quickly become a valued addition on Philadelphia’s waterfront.

“It is indeed a great treat to careworn and busy men and women to be able to shake off toil and trouble for a day and participate in the recreation, change of scene and benefit afforded by The Republic’s breezy sails down the Delaware river and bay,” and to the ocean,” shared a reporter.

“Besides the comfort and conveniences to be found on The Republic, such as splendid meals at regular city, prices, lunches at the restaurant, refreshment stands, and café, all of which are abundantly supplied with the good things of life which the passengers can obtain at moderate cost, the attentions of first-class tonsorial artist in the barber shop.” There’s “excellent entertainment, embracing vocal and instrumental concerts, dramatic shows by funny comedians, vaudeville performances, minstrel shows, and displays of puzzling magic, to say nothing of the privilege of dancing on a fine ballroom floor to the music of a capital orchestra, or taking part in promenades for which The Republic Brass Band furnishes its charming strains.”

“A day can be spent with the utmost satisfaction and the cost is only the round-trip fair, one dollar, with children at half-price, truly a marvelously low figure when the many enjoyments and attractions are considered.”

Indeed, The Republic, this “270-foot 1,285–horse power vessel licensed to carry 2000 passengers daily” had become part of Philadelphia’s life and lore.

Imagine the shock when the steamer with 800 passengers aboard went missing somewhere shy of Cape May on August 23, 1882. “Nothing could be learned of her whereabouts.” The following morning, a large, anxious crowd gathered at the Race Street wharf “to await further news from vessels coming up the river.”

The previous morning, everything started pleasantly enough with the boat assuming “her usual speed” as she paddled downstream. The estimated time of arrival at Cape May: “a little after 1 o’clock.” But about 27 miles from landing mechanical failure brought The Republic to a complete stop. The engineer tried and failed to restore power and Captain Lackey had no choice but to drop anchor, blow off the steam and bank the fires. They then sat and waited “until assistance could be had,” from a passing ship. Help eventually arrived, but the steamer could not be towed to Wilmington, Delaware, the nearest port, until the next day.

Passengers “were not at all alarmed. . . when they found that their trip was spoiled” and that they would “have to make a night of it.” Everyone “proceeded to get their dinner as calmly as though nothing had happened.”

The cabin’s relatively few berths “were at once seized by a person who had charge of a party of women and children. They entered the cabin, closed the door, and sought consolation in sleep.” The vast majority of the passengers made do with “chairs and camp stools”or quiet places on decks where they used life preservers as pillows. Passengers exhausted their picnic baskets before emptying the larders of on-board restaurant. “Nobody went hungry,” though breakfast the next morning “was somewhat meager, consisting principally of crackers and coffee.”

“It was a good-natured, but tired, sleepy, and ‘bedraggled’ crowd that was transferred to the deck of the Felton at Wilmington” for the long awaited return trip to Philadelphia.

Keeping The Republic up and running smoothly was a continuous and necessary challenge. In the 1880s, public memory still resonated with stories of the disastrous and tragic explosion of the steamboat New Jersey on March 15, 1856. Sixty-one passengers died on the Delaware that wintry night.

Maintenance included keeping the wharf and piers in good order. Pile drivers were essential to the process, even with their notorious, persistent and violent “thump . . . thump . . . thump” accompanied by vibrations capable of clearing nearby walls and shelves. Artists and photographers found pile drivers ripe as subject matter. See George Herbert Macrum’s oil painting at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts and Thornton Oakley’s Hog Island – the Pile Drivers at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. So, too, the PhillyHistory photograph of the wharf’s reconstruction in 1896 is both an archival document and, we would argue, a work of art.

[Sources: “Daily Excursions for Cape May,” Inquirer, July 29, 1879; “The Missing Steamer Safe. The Republic’s Machinery Breaks Down – Scenes During the Night,” The New York Times, August 23, 1882; “Something to Think About. The Palace steamer Republic and its Delightful Sails,” Inquirer, August 9, 1891; “Steamer Destroys a Pier,” Inquirer, June 15, 1896; Advertisement, The Philadelphia Times. June 12, 1892.]