Gladys Bentley escaped her family’s North Philadelphia rowhouse at the age of 16 and, for more than a decade, didn’t look back.

She joined the Harlem Renaissance, which in 1923 was kicking into high gear. A jazz performer, Bentley became “one of the boldest performers of her era.” Her reworked popular songs with homespun risqué lyrics packed, among other venues, the notorious Clam House, a speakeasy on 133rd Street. “Bentley sang her bawdy, bossy songs in a thunderous voice, dipping down into a froglike growl or curling upward into a wail” wrote The New York Times in a belated obituary. Appearing in a trademark white top hat and tuxedo, Bentley became Harlem’s most famous lesbian and “one of “the best-known black entertainers” in America.

In 1934, Bentley headlined at New York’s new Ubangi Club, attracting, according to The Philadelphia Tribune, her “Gay White Way clientele that goes all the way to make up New York after dark.” Her act featured “a chorus of boys whose entertaining is of that different style and appeal.”

Langston Hughes would write of Bentley’s “amazing exhibition of musical energy—a large, dark, masculine lady, whose feet pounded the floor while her fingers pounded the keyboard—a perfect piece of African sculpture, animated by her own rhythm.”

Bentley’s return to North Philadelphia in September 1935, at the Memphis Club on Warnock Street below Girard Avenue, was less than a mile from her childhood home. “Miss B is a show in herself,” wrote the Inquirer, “holding the audience from the moment she appears on the floor.”

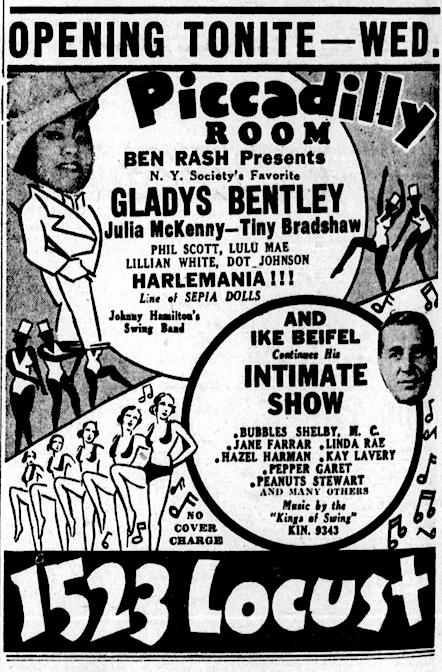

In the summer of 1937, Bentley would perform in Center City at the Piccadilly Room, 1523 Locust Street. Billboard called her billing intriguing, a “noble experiment,” where, in one building, artists of both races performed. The “policy of separate white and Negro niteries under one roof will be tried by 1523 Locust,” reported Variety. One manager ran “colored shows” headlined by Gladys Bentley “presenting the gayest harlemania” in the intimate Piccadilly Room, upstairs front.” Elsewhere in the same building at the same time, Bubbles Shelby was featured as the white headliner.

Bentley quickly drew top billing. She “gives out the risk–gay ditties in that intimate manner that leaves no mistaken meaning. To rousing returns, she offers Just Give It To Tim, Gladys Isn’t Gratis Anymore and a Wally Simpson-inspired He Did It For Love. And for the more intimate circles sings Goody Goody. New to the villagers here, she’s dynamite.”

But the experiment didn’t last. Ann Lewis completed her six-week run at the Piccadilly Room, returned to Harlem, and told a reporter that “racial prejudice is breaking up the management’s attempt to feature…a white and colored revue just opposite each other.” Bentley and others quit the show “when the feeling between the two races became near the breaking point.”

In fact, “the double bill of entertainment” was figured to be “an experiment doomed to failure.”

Philadelphia, “though very much in the North, has always surfaced a definite racial feeling between white and colored” wrote reporter Billy Rowe. “Not many months ago before the passing of the civil rights bill in the state of Pennsylvania, Negroes suffered Jim-Crow tactics used below the Mason-Dixon line in theaters and other Nordic owned enterprises.” After the passing of the Pennsylvania Equal Rights Bill of 1935, the “age-old practice” continued and “as a direct outcome of such fights for equality a new hatred was born in the city of brotherly love.”

Bentley would soon leave New York again, this time for Los Angeles, “to become a leading entertainer there and in the Bay Area,” appearing onstage at Mona’s 440 Club, “the first lesbian bar in San Francisco.” In short order, Mona’s would become Bentley’s West Coast home away from home.

[Sources: “Gladys Bentley Stars at Ubangi Club” in The Philadelphia Tribune, August 23, 1934; “Bentley, Memphis Club,” The Inquirer, September 15, 1935; “Putting White and Negro Niteries Under 1 Roof,” Variety, May 12, 1937; “Night Clubs Star Stage Celebrities in Revue Programs,” The Inquirer, May 12, 1937; “Piccadilly Room, 1523 Club, Philadelphia, The Billboard, June 12, 1937; Billy Rowe, “Black and Tan Revue Can’t Hit: Philly’s Piccadilly Room Tries New Experiment,” The Pittsburgh Courier, July 3, 1937; Giovanni Russonello, “Gladys Bentley (1907-1960): A gender-bending blues performer who became 1920s Harlem royalty.” The New York Times.]

4 replies on “Gladys Bentley and the “Noble Experiment” at 1523 Locust Street”

Thanks, Ken! I knew all about Bentley and her Philadelphia roots and appearances at the Memphis Club and at the Piccadilly Room, but I didn’t know about the racial issue at 1523 Locust.

Thank YOU, Bob. I learned about Bentley from one of your posts not too, too long ago and found the rest as I dug into the stories about her time here in 1937. Should have credited you as a source!

Thanks for this history. Philadelphia was probably the most segregated city in the northeast US, which is saying a lot. South Philly (Italian), Kensington (Irish), Port Richmond (Polish), Northeast Philly (Jewish), North Philly (black), Society Hill, Rittenhouse Square(professional types). My favorite gladys Bentley song was Find Out What He Likes (And How He Likes It). The lyrics would never make it past today’s PC culture. She reminds me of Etta James or Ruth Brown.

Perhaps notable is that Bubbles wasn’t only white, she was Jewish – and looked so (she was married to my dad’s cousin, and died in 2000).