No one had a clue as to what Christopher Columbus actually looked like.

No matter, American artists from Benjamin West onward invented images of Columbus in a host of biographically inspired settings that played both into and off of the truth. Washington Irving’s best-selling biography first issued in 1828 would go through 39 American and 51 international printings popularizing, fictionalizing, mythologizing all the way.

Americans, Thomas Schlereth explains, “configured and contested Columbus differently as a national symbol” in an expanding nation determined to revise, augment, justify and glorify its founding narrative. Columbus served a purpose, appearing again and again, in everything and seemingly everywhere from “painting and philately, monuments and sculpture [to] civic iconography… national coinage, pageants and plays.”

Nineteenth-century America, you might say, discovered Columbus. And in a very real way, writes Schlereth, this century-long, re-creation of Columbus enabled and informed a “larger, many-sided quest for an American national character.”

Where the earliest American monument to the idea of Columbus came in the form of a 40-foot tall obelisk dedicated in Baltimore in 1792, 19th-century Americans would come to expect representations of the person Columbus in the form of statues and busts populating “city parks, civic spaces, and government buildings.”

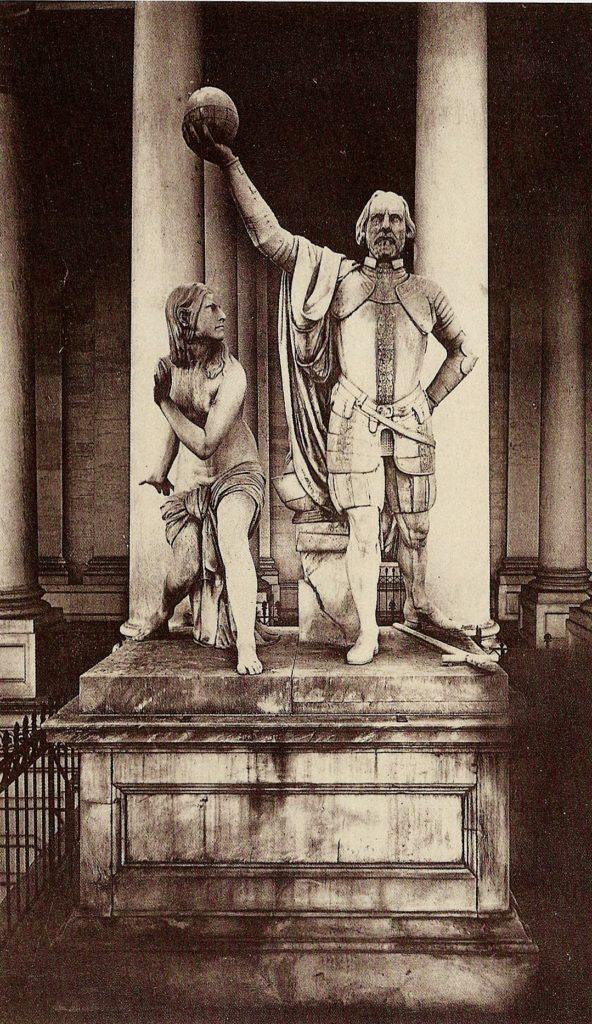

In 1844, Congress dedicated the “first piece of statuary that was ever purchased by the government,” according to William Eleroy Curtis. Luigi Persico’s Discovery of America presented Columbus “clad in a totally inaccurate suit of European armor” carrying in his right hand an orb (“America”) beside “a semi nude Native American female, the Indian princess of colonial America, [who] crouches awkwardly by his side, ready to flee.”

While some accepted the Persico’s sculpture “as an appropriate symbolization of their nation’s manifest destiny and racial supremacy,” as Vivien Green Fryd tells us, others debated the sculpture’s merits, its meaning and its message. Here was another example of “the nation’s perennial search for self-identity.” This time, and in many to follow, it came in a fictional form, figure and face of the so-called “Discoverer.”

By the 400th anniversary of 1492, Schlereth points out, American cities, including Philadelphia, would have 28 monuments to Columbus—more than any other country. Columbus appeared “atop pedestals, fountains, triumphal arches, socles, and freestanding columns.” And for the most part, these depicted Columbus as “independent, destined, and triumphant; he invariably appears as a young, clear-thinking conqueror, the prescient visionary of the first voyage, not the beleaguered mariner of the last expeditions.”

Columbus was no longer abstract; no longer an idea. He was, as Claudia Bushman points out discussing the Persico group at the Capitol in Washington, embodied in a Caucasian male representing racial domination, a statement in stone that, among other things, “underscored and supported the government’s Indian removal policy.” And in the context of the other sculpture flanking the same staircase at the Capitol, Horatio Greenough’s sculpture of a violent encounter between a hatchet-wielding Native American warrior and a Caucasian pioneer family (The Rescue—popularly known as Daniel Boone Protecting His Family), the pair of statues became the target of ongoing controversy.

Both sculptures, according to Bushman,“proved offensive to Americans” and in 1939 a joint congressional resolution proposed “that The Rescue be ‘ground into dust, and scattered to the four winds, that no more remembrance may be perpetuated of our barbaric past, and that it may not be a constant reminder to our American Indian citizens…’.”

The resolution failed to pass. But in 1958, “when the capitol building was to be extended, the government removed all the sculptural works in the vicinity. Most of the art works were later returned to their placed, but the two offending works…disappeared forever.” Word has it they reside in a Smithsonian storage facility somewhere in Maryland. And, since a crane accident in 1976, The Rescue is reduced to a “pile of fragments.”

As for The Discovery Group, its figures stare into the empty space of a warehouse that presumably looks something like the final scene in Raiders of the Lost Ark. Will Philadelphia’s Columbus have a similar fate? Should it?

[Sources: Bushman, Claudia L. America Discovers Columbus: How an Italian Explorer Became an American Hero (Lebanon, N.H.: University Press of New England, 1992); William Eleroy Curtis, “The Columbus Monuments,” The Chautauquan, Vol 16, Oct 1892-March 1893; Vivien Green Fryd, “Two Sculptures for the Capitol: Horatio Greenough’s ‘Rescue’ and Luigi Persico’s ‘Discovery of America,’” The American Art Journal, Vol. 19, No. 2 (Spring, 1987); Thomas J. Schlereth, “Columbia, Columbus, and Columbianism,” The Journal of American History, Dec. 1992, Vol. 79, No. 3.]