At the dawn of the 20th century, tuberculosis mortality rates devastated Philadelphia’s poor Black community. One source claimed the infection rate among Black citizens was three times higher than that of the white population, another reported it was six times greater.

Explanations for this disparity were divided. Some, even from the city’s medical community, upheld the belief that Black people were biologically more susceptible to infection. Others argued that the prevalence of tuberculosis was a consequence of urban poverty, pointing to factors such as overcrowded, poorly ventilated housing, inadequate nutrition and medical care.

James Madison Taylor, an assistant professor of nonpharmaceutical therapeutics at Temple Medical School, was among those who supported the notion of biological susceptibility. He believed that his upbringing on the family plantation in the South gave him special insight into the matter.

“Races of people who have lived for thousands of years in certain climates become adapted to survive and flourish under similar conditions,” wrote Taylor. “They inevitably suffer if suddenly removed to other climates or environments wholly different, for which their structure, skin, color, nostrils, and the like have become entirely unadapted.”

Taylor went even further, claiming that “if they remained in urban settings, the colored people of the United States are in great danger of loss of health, even extinction.” And he concluded with a starkly prejudiced assertion: “All those hordes who are merely eking out a more or less miserable existence in our large cities will disappear. If the Afro-American is to survive or even maintain a fair measure of health, it is imperative that he keep out of the big cities and live in the open country.”

Settlement Archives)

Elizabeth Tyler, a nurse known for her public health fieldwork in Black communities, confidently supported the opposing theory. She and others who actually worked in impoverished urban settings argued that such racist arguments were also factually incorrect. They developed evidence-based responses to counter biases and misconceptions.

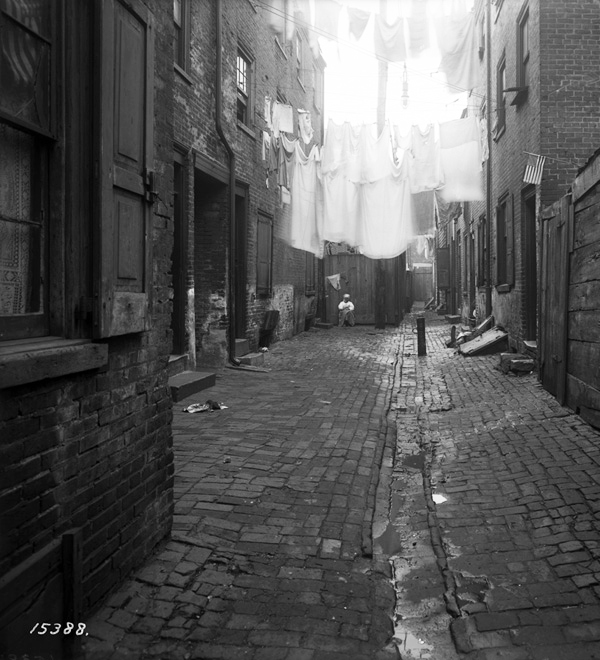

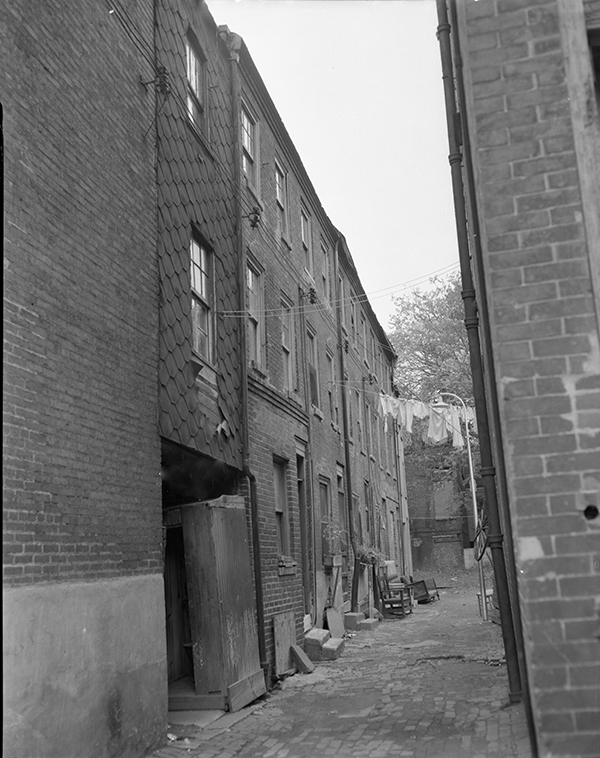

W. E. B. DuBois, for example, conducted his meticulous, door-to-door approach studying Philadelphia’s Seventh Ward. In 1899 he published the groundbreaking work The Philadelphia Negro. A decade later, Dr. Charles A. Lewis, a Black doctor and a prominent critic of the notion that Black individuals were inherently susceptible to tuberculosis successfully persuaded Penn and Lincoln Universities to fund his door-to-door survey of residences between Bainbridge and Fitzwater Streets, from 11th to 12th. According to historian David McBride, Lewis’ findings proved that heightened tuberculosis rates were not due to racial disposition but to the “deplorable conditions under which Negroes were forced to live.”

Philadelphia did not need to purge itself of Black citizens to reduce tuberculosis rates, as Taylor and some others suggested. What the city needed was an informed, scientifically grounded approach to public health. By recognizing and addressing the conditions that contributed to the spread of the disease, Philadelphia could begin to implement a modern, evidence-based public health strategy that would contain and treat tuberculosis.

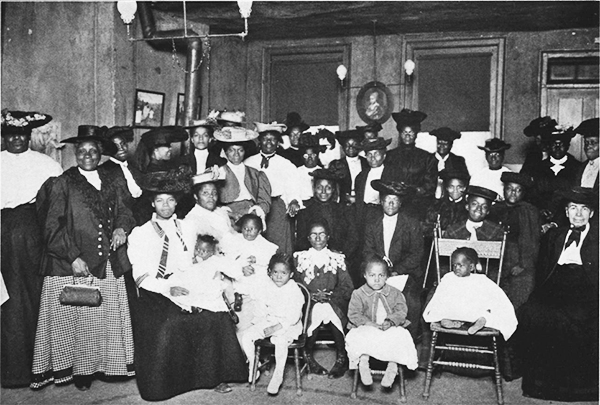

Conditions for change were right at the start of 20th century Philadelphia. Several newly founded African American self-help organizations were flourishing, establishing an increasingly strong foundation for effective public health efforts. The Whittier Centre, founded in 1912, addressed social, health, and housing needs of the Black community. It grew out of the Rainy Day Society and the Cooperative Coal Club, which merged in 1912. These groups had made significant strides, with over 900 members and an active home visit policy. The Whittier Centre’s leaders, led by Dr. Henry R.M. Landis, decided to focus some of the organization’s resources on health issues. He convinced the Whittier board to recruit an experienced Black nurse who would work throughout the community across institutional boundaries.

Landis and his allies believed that a medical professional such as Tyler could establish trust and in ways white nurses could not. A Black nurse, he remarked, could “go with immunity, day or night, into districts in which it would not be safe for a white woman,” and that she could establish “a greater degree of confidence” among Black folks than white nurses had been able to achieve.

Tyler’s experience made her especially qualified. In 1906 she was the first Black visiting nurse at the Henry Street Settlement in New York’s Lower East Side. There she learned street skills including attending church services to listen for tubercular coughs and befriending janitors to help identify infected residents in tenements.

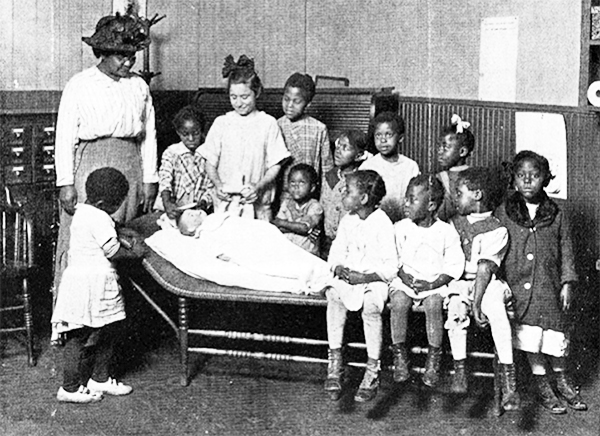

With a clear sense of mission in 1914, Tyler started in Philadelphia with house-to-house visits on the back streets and crowded dead-end courts of the city’s 7th ward. Between March and October she visited 327 families and examined 1,084 individuals, providing medical care and connecting residents to resources including those of the newly opened Phipps Institute. Her door-to-door efforts helped build trust in the community and her work contributed to a dramatic increase in patient visits. She also organized lectures on health in churches and established Little Mother’s Clubs to address the problem of infant mortality. Before a year had passed, the Phipps Institute hired a second Black nurse, Cora Johnson, and its first Black physician, Dr. Henry Minton. This resulted in a twelvefold increase in the number of patients at Phipps compared to the previous decade.

By 1921, Phipps employed six Black nurses and three Black physicians. By that time nearly a third of Phipps patients were Black. Tyler’s efforts initiated expanded public health services where they were most needed. Her work laid the foundation for ongoing outreach services including pre-natal and well-baby clinics and home supervision services. By 1923, when Tyler left Philadelphia to continue her work in Delaware and New Jersey, Phipps was treating more than 3,000 Black patients every year.

Sources: Barbara Bates, Bargaining for Life: A Social History of Tuberculosis, 1876-1938 Series: Studies in Health, Illness, and Caregiving (University of Pennsylvania Press, 1992); Margo Brooks Carthon, “Making Ends Meet: Community Networks and Health Promotion Among Blacks in the City of Brotherly Love.” American Journal of Public Health, Aug 2011 Vol 101, no 8; Rhonda Evans,” Black New York: San Juan Hill and the Black Nurses of the Stillman Settlement,” Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, January 16, 2020); Danina Garcia, “Rare Ability and Devotion”: Elizabeth Tyler, First Visiting Black Nurse of Philadelphia, as Counter-Narrative,” Teachers Institute of Philadelphia (TIP) 2023; H. M. R. Landis, “Tuberculosis and the Negro,” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, November 1928; David McBride, “The Henry Phipps Institute, 1903-1937: Pioneering Tuberculosis Work with an Urban Minority.” Bulletin of the History of Medicine, Vol. 61, No. 1 (Spring 1987), pp. 78-97. The Johns Hopkins University Press; James M. Taylor, “Remarks on the Health of the Colored People” Journal of the National Medical Association, 1915-July, Vol.7 (3), p.160-163.

For more about tuberculosis in Philadelphia: here and here.