Napoleon Bonaparte invaded Egypt with 400 ships, 54,000 men and one artist. Dominique-Vivant Denon “made good use of his time, sketching furiously when the troops paused for brief moments.”

Denon brought back to Paris images far more detailed than the pyramids and broken sculptures Westerners had been familiar with. The 23-volume Description de l’Égypte, published from 1809 to 1828, included no fewer than 837 engravings capturing “Egyptian culture from every possible vantage point.” For the first time, Europeans and Americans could get to know the temples and ruins from Thebes, Esna, Edfu, Philae and more.

These exotic images led to appreciation and emulation in Philadelphia. For the first time, architects could add an Egyptian option to their expanding array of eclectic motifs that included the classical, the Gothic and the Oriental.

What was so appealing to Americans about the Egyptian? Some liked the allusion that their fertile valleys might be compared to the Nile. (The Mississippi was occasionally referred to as the American Nile.) The Schuylkill floodplain near Valley Forge became known as the “Egypt District.” Americans appropriated ancient names: Cairo, Memphis, Thebes, and Karnak – suggesting that their cities might also flourish for millennia.

Americans adopted Egyptian motifs for one cemetery gateway and another. In perpetuity, they would entomb their dead in marble crypts the designs of which were replicated from published sources.

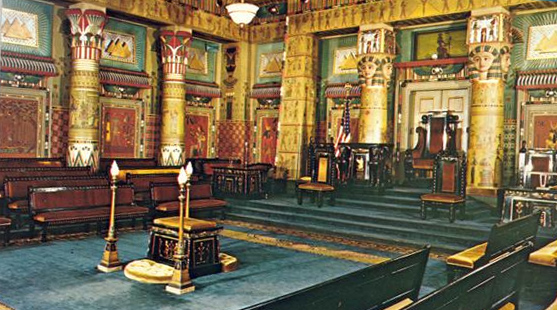

The first American building in the Egyptian style was William Strickland’s Mikveh Israel synagogue on Cherry Street from 1825. Over the next several decades, more Egyptian-inflected buildings would rise in Philadelphia, including a prison, an insurance company, a waterworks, and an Odd Fellow’s Hall (pictured above).

What kept the Egyptian influence from even wider adoption? Possibly the rising anti-slavery movement. After all, wasn’t memorializing ancient Egypt akin to celebrating the institution of slavery? Or maybe Christian America just couldn’t promote Egypt’s pagan past? Whatever–once it took hold, architects, designers and the public couldn’t resist an occasional sampling of the Egyptian option.

One reply on “Exercising the Egyptian Option in Northern Liberties”

https://tile.loc.gov/storage-services/master/pnp/habshaer/pa/pa0800/pa0858/data/pa0858data.pdf This is an 8-page report about the Odd Fellows Hall from the Historical American Buildings (HABS) Survey at the Library of Congress. Text by HABS staffer D.B. Myer in January 1963. It notes that the building was destroyed by fire in 1976. See the entire HABS entry, including images: https://www.loc.gov/item/pa0858/. Thank you, Will Brown.