Thirteen thousand Philadelphians worked for the city at the start of the 20th century, about the same time Lincoln Steffens dubbed Philadelphia “the most corrupt and the most contented” city in America.

How did payroll and patronage play out on the street?

According to historian Walter Licht, an estimated 10,000 city jobs were “distributed to loyal party workers,” who, “in return for employment…pledged portions of their salaries to the political machine, a long-standing practice that had not been ended with reform legislation.” In fact, Licht continued, “investigations revealed that 94 percent of all employees in the city actually paid between 3 and 12 percent of their annual incomes to the coffers of the Republican Party organization for a total take of $349,000.”

Philadelphia was addicted to this corrupt, pay-to play (or pay-to-work) system. Sure, the city “had gone through the motions following the lead of the United States government in establishing a competitive examination system for appointments to federal jobs,” but legislation creating a civil service board for Philadelphia in 1885 “hardly curbed spoilsmanship.” In the City of Brotherly Love “the mayor and his department chiefs were able to bend the system to their needs.”

And everyone knew it. As Theodore Roosevelt put it 1893 (he was an advocate of Civil Service reform): “I should rather have no law than the law you have in Philadelphia. “

In 1905, the “reform forces succeeded once again in securing legislation at the state level” creating “a new civil service commission for Philadelphia, a seemingly more independent agency.” Mayor John Weaver apparently embraced the reform, vacating and replacing leadership and appointing Frank M. Riter to run the new commission. The mayor “annulled” earlier eligible lists” providing Riter with a clean slate and a fully-funded office poised for reorganization and reform. As for his part, Riter was determined to secure “public confidence” having committed his commission to “full publicity and absolute fairness.”

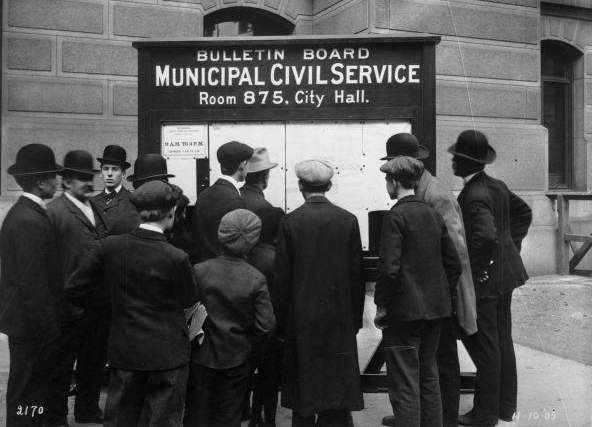

By October, 1905, after Riter’s rash of new civil service examinations had been advertised, implemented and scored, he installed in City Hall courtyard “a large bulletin board…for displaying the results of examinations.” Everyone could read the results whether the positions were guards at the House of Correction, plumbers in the Electrical Bureau, or patrolmen.

Yet the corruption continued. Only a few weeks before the installation of Riter’s bulletin board, the Inquirer revealed that Sheldon Potter, the Director of the Department of Public Safety, “disregarded Civil Service rule” and made appointments only days before receiving the list of eligible candidates from Riter.

The Inquirer also implicated the mayor with circumventing the rules. “Weaver Insincere In Civil Service,” read a headline, “appointments show men with high averages ignored for political favorites.” Civil War veterans had been “especially discriminated against by administration policy.”

“In no respect is the insincerity of so-called ‘reform’ shown up more glaringly than upon the bulletin board of the civil service bureau on the seventh floor of City Hall, the Inquirer pointed out. There can be seen posted long lists of eligibles for various kinds of city positions. … It is here that the utter failure of the administration to live up to its professions of a square deal for every applicant is conspicuously set forth. … A half dozen veterans of the Civil War, standing high on the list have been deliberately passed over and political favorites of the Mayor and his friends, far down on the list, have been given preference. Not only have the veterans been ignored, but other applicants with high averages have been left out and men far below them in the averages of the civil service tests have been given the appointments. … The man with the pull got the job regardless of his special fitness for it, and the man with the high average or near the top of the list has been ignored.”

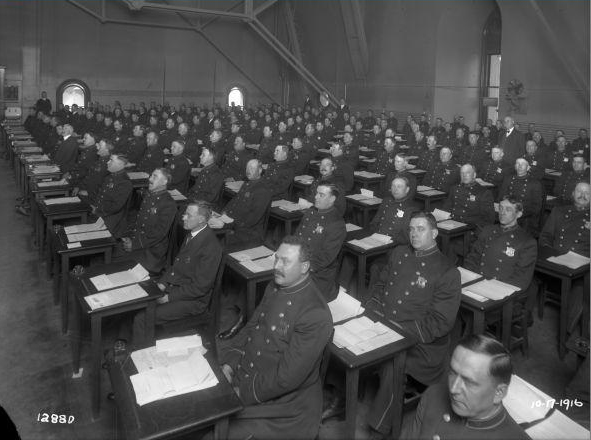

Still, Riter continued as if corruption had been effectively curtailed. His commission continued to offer examinations and to advertise the results. From March through December 1906, Riter’s office tested and scored 4,551 applicants for more than 170 positions—everything from clerks to bricklayers, carpenters to elevator operators, engineers to firemen, patrolmen to drain inspectors, stenographers to telegraph operators, tinsmiths to waitresses.

Who got the jobs? . . . Well, that was not his to say.

[Sources: Walter Licht, Getting Work: Philadelphia, 1840-1950, (University of Pennsylvania Press, 1992)]; “Potter Disregarded Civil Service Rules,”October 7, 1905; “Weaver Insincere In Civil Service,” October 12, 1905; – Riter, the Versatile, Plays Head Waiter,” October 18, 1905; Secretary Riter’s Bulletin Board, October 25, 1905; The First Annual Report of the Civil Service Commission of the City of Philadelphia, Jan 2, 1907. All in The Philadelphia Inquirer; “First Annual Report of the Civil Service Commission of the City of Philadelphia, January 2, 1907” in Annual Message of the Mayor of the City of Philadelphia with the Annual Reports of Directors of Departments, vol. 1 (Philadelphia, 1907).]

One reply on ““The man with the pull” got the job”

The more things change the more they remain the same