“Between four and five thousand babies die annually in this city before they reach their first birthday,” lamented Dr. Wilmer Krusen, the newly installed director of Philadelphia’s Department of Health and Charities in early 1916. “This high mortality is among the ignorant, and is due to ignorance,” Krusen claimed, noting that “half of these were caused by diseases which could have been prevented had the child been given proper medical care and attention.”

“Education is the best factor in the fight to reduce infant mortality” noted Krusen. “Good health instruction centres are to be placed close to the people’s homes” and focus on prevention, “instead of waiting for them to get sick and then seeking help.” In May 1916, Krusen announced the opening of three health centers in as many Philadelphia neighborhoods, all of them intended to educate—and much more. The first of these, Health Center No. 1, would be at 12th and Carpenter Streets in South Philadelphia.

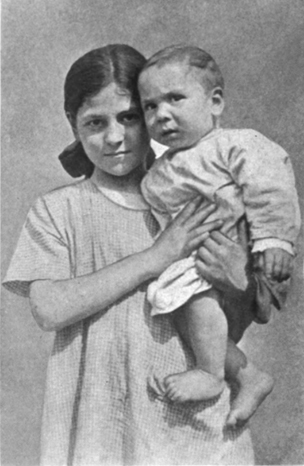

Actually, a non-governmental group called The Child Federation had opened that center at 12th and Carpenter two years earlier—on June 15, 1914. The Federation rented the corner storefront built to serve as a saloon “in one of the most thickly populated districts of Philadelphia, one that contributes largely to the city’s high infant death rate.” Its goals? “To educate and guide new mothers in the feeding and care of their babies” and supervise and educate expectant mothers. This experiment, according to the Federation, would “demonstrate the value of the idea of localized intensive health work. . . not only for Philadelphia, but [also] for other cities.”

“The Health Centre idea is new,” wrote Edward W. Bok, president of The Child Federation and longtime editor of The Ladies’ Home Journal , in 1914. This experimental “comprehensive program,” claimed Bok, would apply “in the community all measures of health protection that are known to science.”

Bok continued: “Before the Centre was formally opened, a preliminary survey of one city block was made with a view to determining its sanitary conditions, the number and size of the families resident in the block, classifying them as fathers, mothers, expectant mothers, school children, children between the ages of 2 and 6 years, and infants under two years of age. … With this data before us,” he wrote, the Federation opened the facility.

“The degree of co-operation that we are receiving from the people in this district has amazed us,” added Bok. “The Centre, as we hoped would be the case, is rapidly developing into a clearing house for the entire community. We are being consulted by the young and the old, male and female, for advice and counsel in regard to all sorts of problems. When we are unable to help them, the applicants are referred to the agencies which can. These experiences are confirming our belief that the only way to satisfactorily solve the health and social problems of a city is to place agencies having the functions of a Health Centre in definitely limited districts of the city.”

Within its first year, Bok and the Federation were able to declare success. “The Health Centre has become in every respect what it set out to be . . . a center for the entire neighborhood.” Two nurses “made 10,142 visits to the homes of the neighborhood, while 10,377 visits have been made by mothers to the Center.” More than 750 families and 491 babies came under the Centre’s care. Prenatal care led to 103 successful births. These results were considered “nothing short of remarkable” and the Federation became “a force in the community life of Philadelphia…”

“Nothing like it has ever been attempted,” reported the Federation. The demonstration site attracted not only city officials, but “physicians and social workers from all parts of the country” who came “to personally investigate” this successful demonstration site in South Philadelphia. “It has attracted country – wide attention,” wrote Bok, “and deservedly so.”

Was it the first of its kind? Bok proudly claimed that the health center at 12th and Carpenter was “the second in name in the United States (New York City had opened a similar facility in Manhattan’s Lower East Side). But this site would be even more comprehensive in the services it offered.

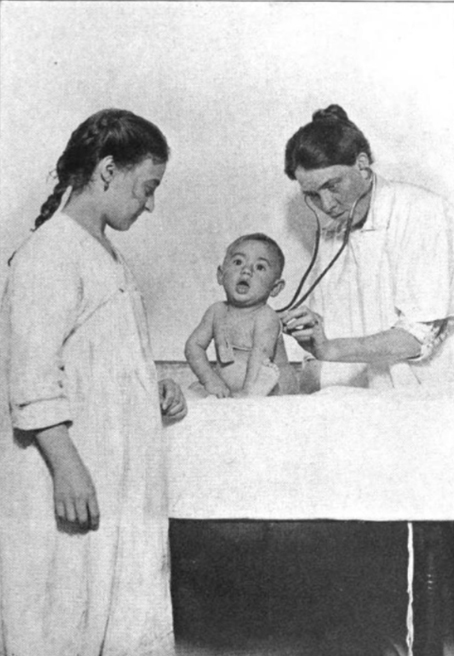

At the heart this success? Neighborhood-oriented, community-based, hands-on nursing. “The health center is a means by which the community is in actual touch with the health nurse and social worker,” wrote Bok. “The visiting nurse, assuming a friendly attitude toward the women of the neighborhood, soon finds their needs. The nurse becomes the confidential friend of the family, learns the family history, the diseases prevalent among the neighbors, the names and location of expectant mothers and sick babies.”

Eliza McKnight, the City Health Department’s supervising nurse, wrote in 1916: “mothers are encouraged to bring young babies to the center once a week, so [nurses] will often detect some slight deficiency that escapes the notice of an untrained parent.” These regular visits to the health centers augmented by the “interest shown in the baby by the doctor or nurse… creates a responsive attitude in the mother.”

“The modern conception of the health center is that it is an institution from which health influences radiate,” according to McKnight. The center would be “a place where people may come to learn how to keep well, the physical expression of creative health effort… the next step in modern preventive medicine.”

As the city’s top public health official, Dr. Krusen quickly realized the value of the Child Federation’s experiment at 12th and Carpenter, but also recognized that this one site was “taxed to the limit.” In the summer of 1916, the city, in collaboration with the Child Federation, would open and staff an additional “five new health centers in congested districts” where “infant mortality is greatest and the general infectious diseases are most prevalent.” Krusen dubbed this aggressive intervention the “Philadelphia plan.”

The plan caught on far and wide. By the end of 1919, 49 communities across the United States boasted health centers and 28 more were proposed in Pittsburgh, Cleveland, Buffalo as well as other cities. By the end of 1920, no less than 385 American communities had health centers all their own.

Where it all started at 12th and Carpenter Streets? Philadelphia’s Health Center No. 1 served its community for many decades before baby care gave way to car repair.

And, we are pleased to report, the original building survives to this day.

[Sources: “Appalling Increase in Infant Mortality”, The Philadelphia Inquirer, July 15, 1910; The First Year Book of The Child Federation Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 1913-14 (1914); The Second Year Book of The Child Federation Philadelphia, Pennsylvania (1915); The Third Year Book of the Child Federation, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania (1916); Eliza McKnight, “Health Centers,” Monthly Bulletin of the Department of Public Health and Charities of the City of Philadelphia, Volume 1, No. 43, April 1916; “Campaign Starts for Better Babies,” The Philadelphia Inquirer, February 2, 1916; “Plan to Reduce Infant Mortality,” The Philadelphia Inquirer, February 28, 1916; “Centres Will Teach Good Health Lessons,” The Philadelphia Inquirer, May 3, 1916; ‘Health District Planned, The Philadelphia Inquirer, May 24, 1916; “Nine Visiting Nurses For City Appointed,” The Philadelphia Inquirer, July 22, 1916; Michael M. Davis, Jr. “The Health Center Idea: A New Development in Public Health Work,” Public Health Nursing, Vol. 8, No. 1, Jan. 1916, pp. 22 – 39; “’Baby Week’ Starts Drive On Ignorance,” Evening Public Ledger, May 1, 1917; Wilmer Krusen, M.D. “The Health Center Plan in Philadelphia,” Health News, Monthly Bulletin, New York State Dept. of Health, Vol. 35, February 1919; “Symposium on the Health Center. I. The Historical Development,” American Journal of Public Health, 11; 1, 1921, pp. 212-213.]

3 replies on “A Surviving Monument to Maternal and Infant Health at 12th and Carpenter Streets”

The death rate of new born babies is staggering. What is equally amazing is that early infant death was an accepted fact and was factored into how many children a family had, especially rural ones who needed help on the farm. Imagine if this were true today. It would be treated as a health care crisis.

Thanks, Mr. Finkel, for your in-depth attention to Philadelphia history:)! This evening, I noticed what looks like a partially extent “H” followed by an intact “D” within an old tiled base next to the doorway of the Health Center building and wondered if you know whether that stands for “Health Department” or may just be coincidental.

Interesting. I would not be surprised if that’s what it is/was.